By Lia N. Poteet, NASA Earth Science, Applied Sciences

February 04, 2021 • As rainfall is increasingly scarce in East Africa, existing groundwater supplies become the main source of water for people, livestock and agriculture. Maintaining access to this life-sustaining resource requires an extensive network of wells and pumps. Earth observations from NASA satellites can indicate that a drought might be on the way – and now, communities can use that information to prepare.

Evan Thomas, a former NASA engineer now at the University of Colorado Boulder, is the lead of the Drought Resilience Impact Platform (DRIP), an international water security partnership of nonprofits, government and research institutions, and principal investigator of the NASA-funded project to incorporate satellite data into DRIP’s efforts.

“DRIP includes partnerships and projects with the Famine Early Warning Systems Network, the Millennium Water Alliance, the Kenya National Drought Management Authority, the Ethiopia Ministry of Water, Irrigation and Energy, and is supported by USAID and NASA,” Thomas said. “NASA’s support helps DRIP create forecasts of groundwater demand and support drought monitoring using satellite data combined with on-the-ground data.”

The NASA-funded grant supporting DRIP is part of the joint NASA-USAID SERVIR program’s efforts to build capacity for Earth observations’ use in decision making around the world. DRIP currently monitors the water supplies of 3 million people via satellite-connected sensors installed on pumps across hundreds of sites in Kenya and Ethiopia. Additionally, current and historic weather data is important for agricultural, climate monitoring and water resource tracking, but that data is largely incomplete for the African continent as weather stations are few and far between. SERVIR is using local rainfall data with DRIP from the research organization Trans-African HydroMeteorological Observatory (TAHMO).

“Working with NASA has allowed TAHMO’s data to be used more widely on the continent – serving thousands more people with local climatological data,” said John Selker, founder of TAHMO. “This data is helping better manage water resources in the region.”

The SERVIR team has developed models for groundwater demand based on Earth observations for parameters like rainfall and surface water from satellite missions including the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument aboard NASA’s Terra satellite. The scientists can also track water levels using NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) mission, which uses gravity to measure changes in water amounts on and below the Earth’s surface, and satellite based soil moisture estimates using synthetic aperture radar data.

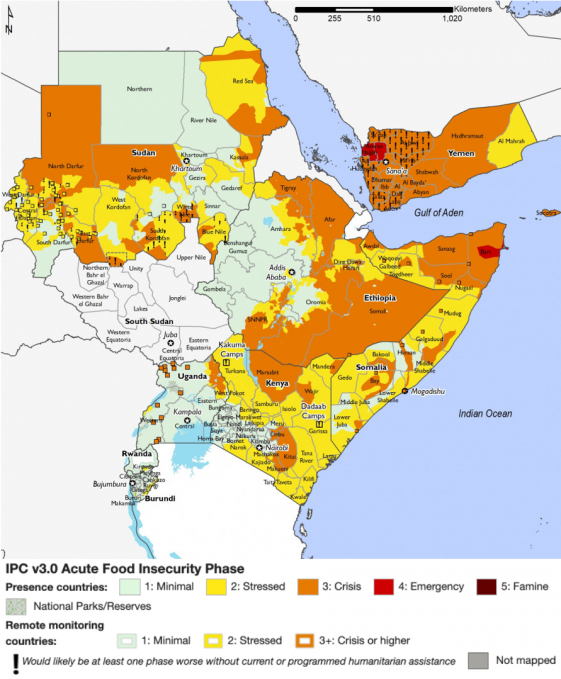

Another planned user of the DRIP system is the USAID and NASA-supported Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET). FEWS NET works with scientists, government ministries and international agencies to track and identify potential food insecurity – and are hoping to use the DRIP platform to inform public reports on conditions in the world’s most food-insecure countries. FEWS NET also uses data from the joint NASA-U.S. Geological Survey Landsat satellite mission.

SERVIR works in partnership with regional organizations around the world to help countries integrate Earth observations into environmental decision-making. Each of these regional “hubs” is hosted by an international technical organization that serves multiple countries within its region.

The SERVIR-Eastern and Southern Africa hub is hosted by the Nairobi, Kenya-based Regional Centre for Mapping of Resources for Development (RCMRD). RCMRD is also a co-developer of the DRIP system.

“Water insecurity is increasing in this region with increased severity and frequency of drought, in part because of climate change,” Thomas said. “DRIP’s work with RCMRD can help increase drought resilience, and NASA satellite data can help us do this cost effectively,” Thomas said.

The project’s goal by 2022 is to establish a groundwater demand service supporting water pump maintenance and drought forecasting across the arid regions of Ethiopia and Kenya.

With advance notice like this, these drought emergencies can be made less dangerous with water resilience efforts; and a combination of early warning data, improved rural water supplies, and maintenance of access points can even be more cost effective than emergency relief like trucking in water. A 2018 study by USAID estimated that, over the long-term, each $1 invested in resilience in areas of recurrent crises would result in nearly $3 savings in averted losses and humanitarian need.

Thomas said that already, thanks to DRIP, resource managers in Ethiopia and Kenya can proactively maintain groundwater pumps and prepare to deliver relief to communities.