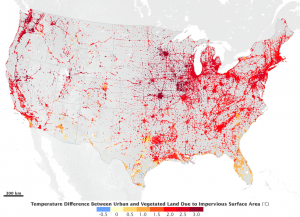

Impervious surfaces’ biggest effect is causing a difference in surface temperature between an urban area and surrounding vegetation. The researchers, who used multiple satellites’ observations of urban areas and their surroundings combined into a model, found that averaged over the continental United States, areas covered in part by impervious surfaces, be they downtowns, suburbs, or interstate roads, had a summer temperature 1.9°C higher than surrounding rural areas. In winter, the temperature difference was 1.5 °C higher in urban areas.

“This has nothing to do with greenhouse gas emissions. It’s in addition to the greenhouse gas effect. This is the land use component only,” said Lahouari Bounoua, research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and lead author of the study.

The study, published this month in Environmental Research Letters, also quantifies how plants within existing urban areas, along roads, in parks and in wooded neighborhoods, for example, regulate the urban heat effect.

“Everybody thinks, ‘urban heat island, things heat up.’ But it’s not as simple as that. The amount and type of vegetation plays a big role in how much the urbanization changes the temperature,” said research scientist and co-author Kurtis Thome of Goddard.

The urban heat island effect occurs primarily during the day when urban impervious surfaces absorb more solar radiation than the surrounding vegetated areas, resulting in a few degrees temperature difference. The urban area has also lost the trees and vegetation that naturally cool the air. As a by-product of photosynthesis, leaves release water back into to the atmosphere in a process called evapotranspiration, which cools the local surface temperature the same way that sweat evaporating off a person’s skin cools them off. Trees with broad leaves, like those found in many deciduous forests on the East coast, have more pores to exchange water than trees with needles, and so have more of a cooling effect.

Impervious surface and vegetation data from NASA/U.S. Geologic Survey’s Landsat 7 Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) sensor and NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) sensors on the Terra and Aqua satellites were combined with NASA’s Simple Biosphere model to recreate the interaction between vegetation, urbanization and the atmosphere at five-kilometer resolution and at half-hour time steps across the continental United States for the year 2001. The temperatures associated with urban heat islands range within a couple degrees, even within a city, with temperatures peaking in the central, often tree-free downtown and tapering out over tree-rich neighborhoods often found in the suburbs.

The northeast I-95 corridor, Baltimore-Washington, Atlanta and the I-85 corridor in the southeast, and the major cities and roads of the Midwest and West Coast show the highest urban temperatures relative to their surrounding rural areas. Smaller cities have less pronounced increases in temperature compared to the surrounding areas. In cities like Phoenix built in the desert, the urban area actually has a cooling effect because of irrigated lawns and trees that wouldn’t be there without the city.

“Anywhere in the U.S. small cities generate less heat than mega-cities,” said Bounoua. The reason is the effect vegetation has on keeping a lid on rising temperatures.

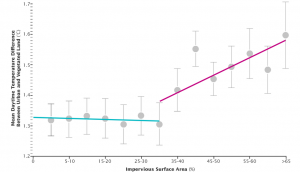

Bounoua and his colleagues used the model environment to simulate what the temperature would be for a city if all the impervious surfaces were replaced with vegetation. Then slowly they began reintroducing the urban impervious surfaces one percentage point at a time, to see how the temperature rose as vegetation decreased and impervious surfaces expanded.

At the human level, a rise of 1°C can raise energy demands for air conditioning in the summer from 5 to 20 percent in the United States, according the Environmental Protection Agency. So even though 0.3°C may seem like a small difference, it still may have impact on energy use, said Bounoua, especially when urban heat island effects are exacerbated by global temperature rises due to climate change.

Understanding the tradeoffs between urban surfaces and vegetation may help city planners in the future mitigate some of the heating effects, said Thome.

“Urbanization is a good thing,” said Bounoua. “It brings a lot of people together in a small area. Share the road, share the work, share the building. But we could probably do it a little bit better.”

Further Reading:

+ Read the paper at Environmental Research Letters

+ Vegetation Limits City Warming Effects

+ Ecosystem, Vegetation Affect Intensity of Urban Heat Island Effect

+ Urban Rain

+ Beating the Heat in the World’s Biggest Cities

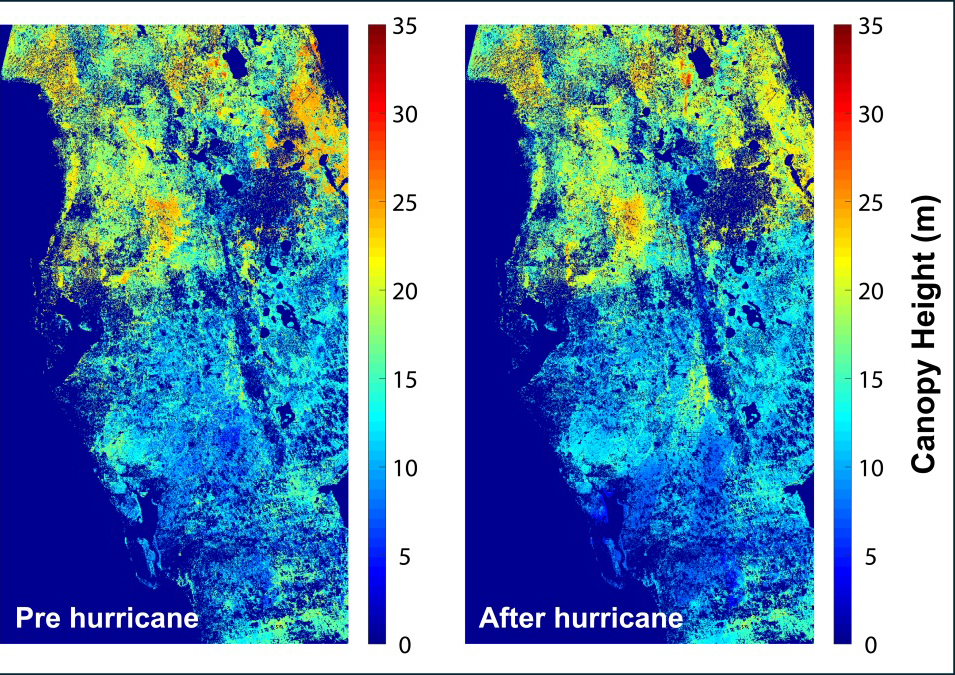

Mapping Forest Damage from Hurricane Milton on Florida’s West Coast

Rising sea levels and increased ocean temperatures are supercharging hurricanes. Using satellite data can help monitor vulnerable ecosystems.