Source: NASA’s Curious Universe

Farmers rely on the accuracy of a crucial NASA and USGS mission, Landsat, to make decisions about crops. Those decisions have far-reaching implications that can impact what you see on your dinner plate.

To learn more listen to NASA’s Curious Universe podcast about Landsat!

Listen now.

TRANSCRIPT:

[MUSICAL INTRO: “Antechamber Underscore” ]

DAVID JOHNSON: I really like to think of Landsat as a, as a very sophisticated smartphone camera orbiting the Earth. Every 16 days, it has fully captured imagery from all over the globe… DAVID JOHNSON: I can literally drive around the Corn Belt and I’ve done this at times.

[CAR NOISES UP // PICKUP TRUCK TURNS ON]

DAVID JOHNSON: And see what’s going on in the ground. And then also see it in the Landsat imagery. And it’s a verification that what we see in the imagery is actually what’s happening on the ground…

HOST PADI BOYD: This is NASA’s Curious Universe. Our universe is a wild and wonderful place. I’m Padi Boyd, and in this podcast, NASA is your tour guide.

HOST PADI BOYD: In this episode, we’re going out to space. But not too far beyond our atmosphere, we’re gonna turn back around, and take a look at Earth. We’re exploring how data collected from space can help farmers on the ground.

HOST PADI BOYD: We’re talking about a mission called Landsat.

[MUSICAL TRANSITION]

JIM IRONS: ..NASA is engaged in the Landsat program because we observe the eEarth from space. We observe it for many purposes. We observe it to help understand the atmosphere and how it’s changing, the oceans and how the oceans are changing, and the impact of humans on our resources and how we use those resources…

HOST PADI BOYD: That’s Jim Irons. He’s the director of the Earth Sciences division at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and also the project scientist for Landsat 8.

HOST PADI BOYD: Landsat is a joint mission of NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey, or USGS. It holds the title for the longest continuous record of our home planet’s surface from space. Since 1970, Landsat has archived images and data of Earth, offering scientists information about how our world is changing. But it also does something pretty surprising. This data … helps farmers.

JIM IRONS: …A farmer can look at Landsat data and determine basically how well their crops are doing. They can look at the crop report from the National Agricultural Statistical Service and determine who is growing or what crops are being grown in their region or across the country so they can make decisions about planting in the next year…

HOST PADI BOYD: We can learn a lot from Landsat data and imagery. DAVID JOHNSON: …We use the imagery to literally try to establish what type of crop is growing in every field across the United States …. to identify that field as corn or soybeans or wheat or cotton rice, go on down the list….

HOST PADI BOYD: David Johnson works for NASS, the National Agricultural Statistics Service. He’s a geographer and also a member of the Landsat science team. He says that Landsat imagery is crucial to the information NASS provides to farmers and consumers. DAVID JOHNSON: Once we establish what we think is growing in each field, we aggregate that up to come up with a statistic for the amount of corn area in a state like Iowa, or soybean area in a state like Illinois, or wheat in their state like Kansas. It’s really for all the states, all the crops..

HOST PADI BOYD: Farmers rely on this information to make decisions about crops. Those decisions have far-reaching implications that can even impact what you see on your dinner plate! DAVID JOHNSON: So it ends up impacting commodity prices as people try to understand if there’s gonna be an extra supply of grain in a given year or maybe a deficit of grain in a given year. So Landsat is another tool in our disposal that helps us get at those area estimates!

HOST PADI BOYD: Landsat is one mission that provides us with a long record of information about the health and changes of our planet. So much so that it’s hard to picture a world without it!

HOST PADI BOYD: But to really understand Landsat, we have to step back in time. And look at where it began. DAVID: I would say Landsat was way ahead of its time when it was first conceived and launched what’s really, almost 50 years ago. …

HOST PADI BOYD: When it began in the 1960s, the program was still called Earth Resource Technology Satellites.

HOST PADI BOYD: We tracked down someone who was there at the very beginning.

HOST PADI BOYD: Valerie Thomas. Before she got to NASA, Valerie had never even seen a computer before. So she started from scratch, learning everything she could about them.

HOST PADI BOYD: Valerie recorded her end of this interview on an old tape cassette recorder….

VALERIE THOMAS: First of all, I was an only child. And I was very curious. …now my father was into electronics, electronics and photography…

VALERIE THOMAS: …When I first went to the library…And I came across the book and I was so excited…”The Boy’s First Book in Electronics.” And I looked through and I saw these projects, and all I could think about was taking this home and the father’s tell me how to do this project. I took it home. My father said, “Oh, I can do that. And I can do that. I can do that.” But he didn’t show me how to do anything…So my book ended up sitting on the table, or wherever it was, until it was time to return it to the library.

VALERIE THOMAS: And I sort of got the impression that … that was my father’s way of saying electronics is not for girls. Just go and do what your mother does — sewing, and hair, which I did. But I still wanted to know about electronics…I wanted to know what made things tick…

[MUSICAL UPTICK]

VALERIE THOMAS: …My pursuit and growing up and going through college prepared me to not be afraid of the unknown … and to try to figure things out.

HOST PADI BOYD: That pursuit got Valerie to NASA just a few years before the Landsat Program started. She was tasked to work on LACIE, a solution to a problem the US was facing…

JIM IRONS: When the first Landsat satellite was launched in 1972, it occurred just after an event that became known euphemistically as the Great Grain Robbery. VALERIE: During that time, the U.S. stockpiled a lot of wheat and if another country was having a problem with wheat yield or some other problems with crop failure, they could contact the U.S. and the U.S. would make some available to them. So, there was a project that was started, based on the crop failure in wheat in one of the large countries and they wanted a lot. Turns out it was so much that it caused a lot of problems for the US to be able to satisfy the requirement…

JIM IRONS: ….Crops had failed all over the world. Great wheat crops in particular And there was going to be a shortage of wheat in places in other places in the world. But the US had done relatively well and had a lot of wheat grain stored up. The nation wasn’t aware of the problem in the rest of the world and sold the grain from our storage at a relatively low price, in fact, a real low price. And it turned out that our farmers could have made a lot more money if they had known of the shortage… VA

LERIE: There was a project that I worked on called LACIE. Large Area Crop Inventory Experiment…

JIM IRONS: And when my first semester in grad school I was given the opportunity to go down to JSC where LACIE was organized, it was a multi-agency organization, and learn a bit about how that effort was being approached….

HOST PADI BOYD: LACIE was a project that showed for the first time that global crop monitoring could be done with Landsat satellite imagery. That there was a way for the US to keep an eye on our crop from a global scale.

JIM IRONS: When I went to JSC and started being introduced to people working on Landsat data, they assigned me a supervisor. He convinced me and about how important the observations from space in general and how the Landsat program in particular, how exciting it was and how it was the future of Earth science to a large degree and how it would drive what we would learn and understand about the Earth, from this point forward….

HOST PADI BOYD: And to say that wasn’t an overstatement. Landsat really did drive many of our discoveries about Earth.

JIM IRONS: The whole point of the program and the reason it’s important to NASA and to the nation and for that matter to the world, is that we’re trying to understand the state of the Earth — of the Earth system, and how it is changing over time.

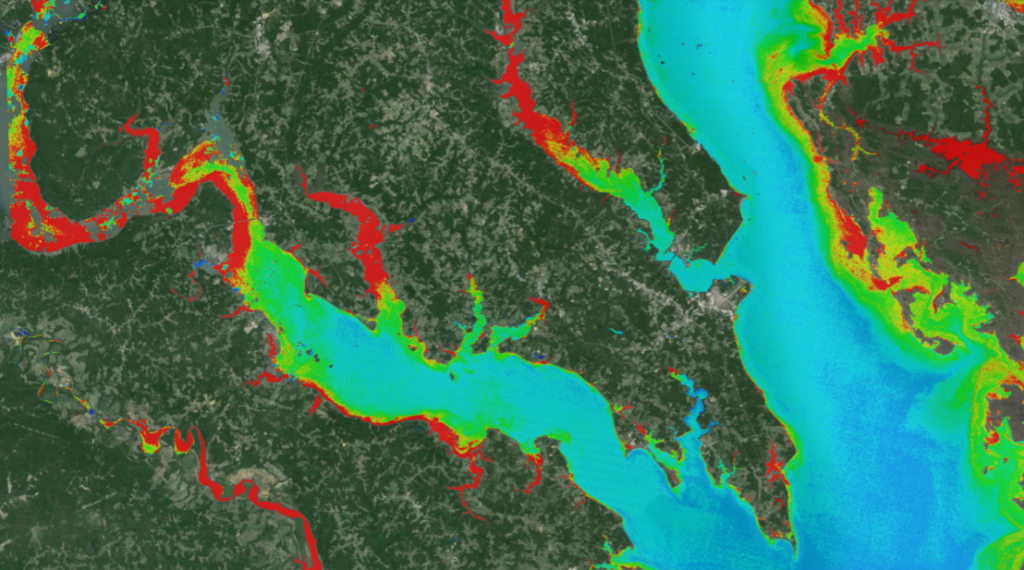

HOST PADI BOYD: …Landsat helps us do that in a unique way. The imagery we get from Landsat goes beyond what the human eye can see. Even though it uses technology we’re all familiar with.

HOST PADI BOYD: While Landsat provides compelling images of the Earth’s surface from space, its sensors are actually well calibrated scientific instruments! DAVID JOHNSON: I really like to think of Landsat as a, as a very sophisticated smartphone camera orbiting the Earth. It captures not only visible imagery, so what you and I would see with our eyes, but also parts of the electromagnetic spectrum in the near infrared and thermal, infrared….

JIM IRONS: So a Landsat image looks a lot like a digital image, maybe taken from very high up over the surface of the earth. The difference is that your digital camera records information for the blue, green and red portion of the spectrum that matches the response of our eye.

HOST PADI BOYD: The Landsat satellites go beyond what our eye is able to see. So, Landsat collects images for that visible portion of the spectrum, but also gives us a lot more information. It goes into the infrared, where our eyes are not as sensitive.

HOST PADI BOYD: If you wanted to look at a Landsat image to get an idea about the state of the Earth, you can combine information from the multiple wavelengths of light that go beyond what our eyes can see. We call those false color images. And they can tell us about crop health.

JIM IRONS: …And those false color images have the ability to emphasize or highlight certain features of the Earth. DAVID JOHNSON: And it’s those aspects that really help us get a strong clue about crop health, crop progress, crop condition…

JIM IRONS: And we can train computers to recognize those patterns and then produce maps that show the different types of land cover, the different types of vegetation on the surface of the Earth…

JIM IRONS: …And you start combining multiple images of the same area taken over time, then you can analyze how those patterns are changing over time and then infer even more information about the surface of the Earth. DAVID JOHNSON: We’re closing in on 50 years of Landsat-type imagery. And so it’s the digital imagery that we can piece together an overlay from back in the back in time with the current date, to give us an idea how things have changed in terms of where crops are being grown. If the crop health is better this year than it was last year, or 10 years ago….

[SONIFICATION KICKS OFF, STRUMMING NOTES ON A GUITAR]

HOST PADI BOYD: And that record of information helps us keep track of the Earth’s changes.

HOST PADI BOYD: We can see a lot from Landsat data. And we can make music with it, too! Let’s take a listen to what a long record of Landsat data might sound like.

[SONIFICATION]

HOST PADI BOYD: You hear that? The high-pitched strings plucked periodically indicate the acres of land where six of the world’s major crops are grown—those are corn, soybeans, wheat, alfalfa, cotton, sorghum.

HOST PADI BOYD: The higher the pitch, the more acreage Landsat recorded. Every slap of the guitar is a year. Starting in 1995.

HOST PADI BOYD: Let’s listen again, with that in mind.

[SONIFICATION KICKS OFF, STRUMMING NOTES ON A GUITAR]

HOST PADI BOYD: What you just heard is called a data sonification — music driven by data, like a chart for your ears. Listening to data helps us think about it in new ways.

HOST PADI BOYD: Like in this one, you can hear the acreage growing as the pitch of the guitar strings get higher.

[SONIFICATION FADES OUT]

HOST PADI BOYD: Now, we can look at decades of information on crop health with accuracy.

HOST PADI BOYD: But that wasn’t always the case. The Landsat program’s early technology paved the way for that possibility. DAVID JOHNSON: Landsat was digital way before most of us knew what a digital camera was. So it really was ahead of its time…

HOST PADI BOYD: There’s a lot we can tell from Landsat data and imagery today, but the program had humble beginnings. It took a few visionaries, like Valerie, to set the groundwork.

VALERIE THOMAS: I got on Landsat in 1970. The first Landsat was launched in 1972, so I got in on that project at a very early stage.

VALERIE THOMAS: During that time, to write programs, you had to be either a mathematician, engineer, or scientist. It turns out during that time, there were no computers at people’s desks. The computer was in another building.

VALERIE THOMAS: They had a key punch machine because we were still doing key punches, with key punch cards. So it was a very different time then. There weren’t these various apps and operations and other kinds of things that people use now…

JIM IRONS: Back in those days, Landsat scenes were analyzed almost one at a time. Some of it was computerized analysis, but it was slow….

[Archival] Daily, a mounting volume of imagery going to a long list of subscribers, at universities and research agencies, as well as individuals around the world, providing us with a more complete view of that world than we’ve ever had before…

JIM IRONS: …When I first started working with Landsat data, we’d print out information on an alphanumeric printer, on long strips of computer paper.

[Archival] Man began the first comprehensive inventory of his earthly resources and he launched a valuable new means of obtaining info needed to manage those resources for his future wellbeing.

JIM IRONS: And we’d hang those printouts on a wall and sometimes color them in with magic marker or colored pencils….

[UPSWELL in ARCHIVAL] A new chapter in space, is in fact, a new chapter in man’s effort to prove himself worthy of his earthly heritage…

JIM IRONS: When I got back to Penn State, I was really ahead of the game. I would watch a single image drop into a television display like one line of pixels at a time, and then I would work at night and turn off the lights so I could record those maps on a film camera and then tape them into my thesis…

DAVID JOHNSON: …It took awhile for the infrastructure for computing to catch up to that, and but with the really the foresight, those minds and engineers have in the past the histori

cal data is, is it’s very important also, because we need to look in the past to get an idea of what’s happening and current in the current day and for understanding if something really is an anomaly or not.

HOST PADI BOYD: Thanks to that long record of data, We can see things like spikes and anomalies. We can track changes over time.

HOST PADI BOYD: And we can ensure there’s not another Great Grain Robbery, because we can track how our crop health and supply are changing over time.

HOST PADI BOYD: Eight Landsat satellites have been launched since 1972, and NASA plans to launch a new one in Fall of 2021, Landsat 9, which will continue Landsat’s legacy and contributions to us here on Earth..

JIM IRONS: The technology has just grown over my career in ways that I had never imagined. But I think some of the people who began the Landsat program back in the 60s, maybe they were more prescient than I ever was and kind of envisioned the growth of the program, the growth of the technology as it is today…

[CREDITS]

HOST PADI BOYD: This is NASA’s Curious Universe. The Curious Universe team includes Klaus Mayr, Micheala Sosby, Margot Wohl, and Vicky Woodburn. Our executive producer is Katie Atkinson.

HOST PADI BOYD: Special thanks to Ryland Heagy, Matt Russo and Andrew Santaguida of System Sounds, Mike Velle (Vell-EE) and the Landsat team. If you liked this episode, please let us know by leaving us a review, tweeting about the show @ NASA, and sharing us with a friend…

[MUSIC FADE OUT]

[TAPE RECORDER CLICK]

VALERIE THOMAS: Overall, the project was excellent. When I was going through it, I felt like the female version of superman. Able to jump over tall buildings in a single bounce, and faster than a speeding bullet… That’s what I felt like.

[TAPE RECORDER CLICK]

[PAUSE]

HOST PADI BOYD: Still curious about NASA? You can send us questions about this episode or a previous one and we’ll try to track down the answers!

HOST PADI BOYD: You can email a voice recording or send a written note to NASA-CuriousUniverse@mail.NASA.gov. Go to nasa.gov/curiousuniverse for more information.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.