Source: NASA Earth

April 14, 2020 • It’s a massive, marvelous planet we live on, and part of what makes it so wonderful is the fascinating array of wildlife.

That wildlife may not be the first thing that comes to mind when you think of NASA, but researchers and conservationists around the world are using data and images from NASA satellite instruments to manage and track living creatures of all kinds.

Conservationists in Kenya are finding new habitats for endangered black rhinos by using a tool that helps them track changes to landscapes in NASA satellite images. A scientist at Stony Brook University in New York is using a program that analyzes NASA satellite imagery to help track the movement of penguins in Antarctica.

Leading the Charge to Find Rhino Habitats

After careful conservation efforts to bring rhinos back from the brink of extinction, extreme weather is making it difficult to provide a habitat for them to thrive in.

For conservationists in Kenya, analysis of satellite data from the joint NASA/U.S. Geological Survey Landsat program using a tool called the Africa Regional Data Cube (ARDC) could provide answers.

Located in northern Kenya, Il Ngwesi Conservancy is home to the Il Lakipiak Maasai people, who set aside 80 percent of their community land to provide wildlife with protected grounds within which animals could roam freely without the threat of poachers.

Rhinos have been critically endangered by a half century of poaching, with numbers in Kenya falling from 20,000 in the 1970s. A painstaking conservation effort has raised the number to about 650 black rhinos.

“This community knows its lands and animals,” said Mohammed Shibia of Northern Rangelands Trust, which supports 39 conservancies in the region. “Where once the Maasai boys in the community would collect information on water availability and suitable grazing pastures throughout a reliable seasonal cycle, now with frequent flooding and drought this becomes an impossible task. Remote sensing can be a highly effective tool to manage great swathes of land without causing exhaustion and hardship.”

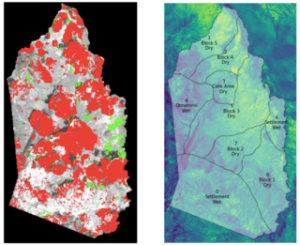

Now Shibia is working with Il Ngwesi leaders, neighboring conservancies in Lewaand Borana, and local and international organizations to derive insights from satellite data and develop a plan to protect and preserve land with the preferred environmental and climactic conditions for the rhinos. The landscape being monitored is large — about 35 square miles, divided into 9 grazing plots, through which pastoralist communities pass and animals roam.

The research team is using the Africa Regional Data Cube (ARDC), an initiative developed by a host of partners including the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data (a network of 250 organizations working to improve data for international development), NASA, Committee for Earth Observation Satellite (CEOS) and others that provides an analysis-ready platform that can be used to look back over 20 years of satellite data and identify changes in rainfall and the vegetation state of the grazing land.

Demand for satellite data by governments in low income settings is high — areas of interest include everything from identifying physical destruction of lands caused by illegal mining, to monitoring deforestation, drought conditions, coastal erosion and showing urban sprawl in growing cities over time. A coalition of international organizations is rolling out a continental wide data cube in 2020 through the Digital Earth Africa initiative. Input and feedback from the five countries using the ARDC — Kenya, Ghana, Tanzania, Senegal and Sierra Leone — helps develop products and algorithms that are shared openly as global public goods.

For Il Ngwesi, time series data analysis on changing vegetation availability over time will be consolidated into reports and shared with neighboring conservancies, partners and Kenya Wildlife Service, strengthening coordinated action and building the licensing application to host additional black rhinos. There are two rhinos onsite and the plan is to host 10 more rhinos in the short term, building up to an eventual population of 30.

“Using remotely sensed estimates of Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) we can see which of these grazing plots are losing vegetation, through fluctuating weather conditions or over-grazing, over time.” said Brian Killough, a researcher at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, who led the technical development of the ARDC. “Using the data cube, the Il Ngwesi and Northern Rangelands Trust are able to observe and anticipate trends in vegetation condition to identify plots most suitable for the rhinos and develop grazing plans to prevent decimation of the lands, which could impact the health of the people and animals using it.”

— Jennifer Oldfield, Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data

Counting Penguins

Heather Lynch, a professor at Stony Brook University in New York, has dedicated her career to answering a very specific question: Where are all the Antarctic penguins?

To help answer that question, L

ynch and her team use advanced software and citizen science efforts to comb through satellite and aircraft imagery and pinpoint penguin guano, or droppings. Since penguins don’t move around very much when they’re not in the water, “they have a lot of pooping to do,” said Alex Borowicz, a graduate student with Lynch.

Understanding where these small birds live helps Lynch and other researchers understand the effects of climate change on underlying ocean ecosystems. “Penguins help us track any major changes in the food web,” Lynch said. Individual species of penguins also react to climate change in different ways, Lynch said. Emperor and Adelie penguins have typically struggled in warmer temperatures, while Gentoo penguins have expanded their population and range.

“Penguins are one of the only species that are visible in the Antarctic,” Borowicz said. Penguins are unique because they sit on nests all summer and don’t move around very much, while seals, whales and flying birds are either in the ocean or on the move, which makes them harder to track. All other life is microscopic or lives under the water.

Knowing what penguins are eating and doing helps us understand what’s happening to all the other species we can’t see, he said.

To help determine how many penguins are living in the frigid, windy Antarctic, the team encourages citizen scientists to join the effort from the comfort of their own homes. “People want to look for penguins,” Lynch said.

Artificial intelligence software helps, too. In March 2018, the team used software to discover that a suspected penguin colony was in fact a booming colony with more than a million Adélie penguins on the Danger Islands in the Weddell Sea just off the northern Antarctic Peninsula.

“We developed an algorithm to have a computer analyze Landsat imagery for Adélie penguins,” Lynch said. When it spotted guano, the telltale sign of a penguin colony, “We initially thought it was a mistake with the algorithm.”

The team confirmed the presence was real with high-resolution commercial satellite imagery, which identified the guano more clearly, and ultimately with an expedition to the region to actually see the penguins.

The team’s Adélie penguin discovery on the Danger Islands led to an expansion of the proposed protected area currently being negotiated for the region. In fact, advanced software has been applied to a number of southern hemisphere bird species, helping us improve the accuracy of their distribution maps. Lynch aspires to this kind of connection between science and policy. “Since we are going to set aside marine protected areas, we need to set aside the right ones,” Lynch said. “Satellites are now playing a huge role in making sure that’s the case.” — Elizabeth Goldbaum

Bringing Birds and Farmers Together

With the majority of lands in the U.S. privately owned, and populations of many plants and animals in steep decline, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) has sought new ways to engage private landowners to take actions to benefit biodiversity and ensure conservation investments match the scale of nature’s 21st-century needs. Landowners need approaches that allow flexibility and provide incentives for them to change how they manage their lands and water.

“One of the places we zeroed in on is California’s Great Central Valley,” said Mark Reynolds, a TNC scientist. “We saw a lot of opportunity there to develop a program that would be mutually beneficial to wildlife and farmers.”

That program is called BirdReturns. Now in its sixth year, BirdReturns helps provide habitats for migratory shorebirds and other waterbirds at farms in the Great Central Valley.

Shorebirds depend on shallow-water habitats for foraging and resting. In collaboration with Point Blue Conservation Science, TNC developed an approach for classifying satellite images from the joint NASA/U.S. Geological Survey Landsat program to characterize surface water availability in the Central Valley, enabling a large-scale multi-seasonal assessment of potential habitats for shorebirds and other waterbirds.

TNC uses predictive models of bird species occurrence and abundance developed with data from the citizen science project eBird, an online checklist program of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in which citizen observers document the presence or absence of species of birds throughout the year.

BirdReturns combines predictive models, legacy and real-time monitoring data on birds and habitat with a market-based conservation approach. Through BirdReturns, farmers participate in a habitat auction in which their rice fields are selected to create high quality temporary habitats when and where they’re most needed for migratory waterbirds. The farmers keep their fields flooded for an additional period of time to provide the habitats.

Through this program, the Conservancy has cost-effectively provisioned more than 50,000 acres of temporary habitat for migratory birds in California’s Great Central Valley – a globally important migration and wintering area for ducks, geese, and shorebirds.

— Mark Reynolds/Joe Atkinson