By Madeleine Gregory

In the young trees of the frigid boreal forests lurks the potential to draw carbon from the atmosphere. As trees grow, they sequester carbon in their woody tissue; the question is how much these forests can grow and where this growth is occurring. New research led by Landsat 8/9 Project Scientist Chris Neigh used Landsat and ICESat-2 data to investigate this question. The study, published in January in Nature Communications Earth and Environment, is the first known empirical circumpolar-scale exploration of the capacity of land to grow trees.

The boreal biome is a massive stretch of forest in the northern latitudes, spanning from North America across northern Europe and Asia. Boreal forests account for a third of the globe’s forested area, and they are warming faster than any other forest. These changes have paved the way for more tree growth in the region. A team of scientists—including six co-authors from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center—found that this newfound growth could translate into increased potential for the region to act as a carbon sink. Russia had the strongest potential for forest growth, with 73% of the possible change in Russia’s forests.

Estimating potential forest growth from space is no easy feat. First, researchers need to know how tall trees currently are over a vast domain. For measures of current forest height, the team turned to ICESat-2, which uses laser pulses to measure the height of features on land. They compared these heights with Landsat-derived estimates of forest age and disturbance. Knowing how tall and old each forest stand was gave the researchers a baseline. Then, they subtracted how tall the forest currently is from how tall it could be, getting an estimate of how much the forest could grow over time.

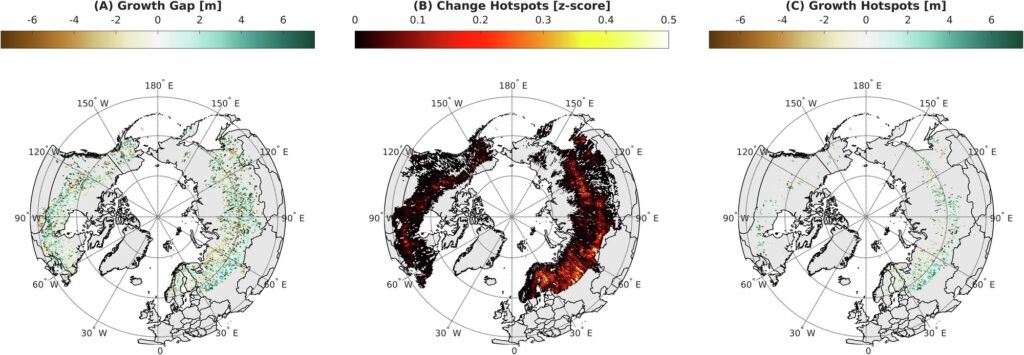

To understand forest dynamics over decades, the researchers used Landsat data to analyze tree cover annually from 1984-2020. They filtered through nearly forty years of data to find images of the highest quality, selecting summertime images with few clouds. From the 224,026 images they selected for analysis, they estimated forest age and disturbance over decades. Then, they combined this data with forest height data from ICESat-2, determining how tall forests of various ages were. Using a range of forest growth models, they mapped expected forest height across the entire boreal biome. They found growth hotspots across the boreal region where disturbed forests could grow taller if allowed to recover. Those hotspots were centered in southwestern Russia, where forests could grow an average of two to almost five meters taller.

“Pairing Landsat age estimates with ICESat-2 height estimates provides scientists with a powerful global tool to understand forest resources and the carbon cycle, which is important to understand where and how fast carbon in the atmosphere could potentially be stored in wood biomass,” Neigh said.

So what does that mean for the region’s future as a carbon sink? If allowed to recover from disturbance and continue to grow, the boreal forest could sequester a large amount of CO2. Exactly how much is still an open question, one that Neigh and his team are investigating in other research. The boreal biome is already an important carbon sink: The trees and vegetation store around 38 petagrams of carbon, while the soils beneath store a whopping 1,672 petagrams of carbon. For reference, humans burned a total of 11.14 petagrams of carbon in 2023. The boreal forest represents 20% of the total global forest carbon sink, including 50% of all global soil carbon, most of which is trapped in frozen soil. The biome has warmed 1.4°C over the past century, and future warming threatens to release some of the carbon in that frozen soil back into the atmosphere.

Ecosystems are changing rapidly, especially in the fast-warming northern latitudes. Because many boreal forests are remote and hard to reach, satellite data is a critical tool for researchers and land managers to understand the changes happening in these ecosystems. By combining data from different NASA satellites—as this work does with Landsat and ICESat-2—scientists can get a unique vantage on the rapidly changing boreal ecosystems.

Reference

Neigh, C.; Montesano, P. M.; Sexton, J. O.; Wooten, M.; Wagner, W.; Feng, M.; Carvalhais, N.; Calle, L.; Carroll, M. L. Russian Forests Show Strong Potential for Young Forest Growth. Communications Earth & Environment 2025, 6, 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02006-9.