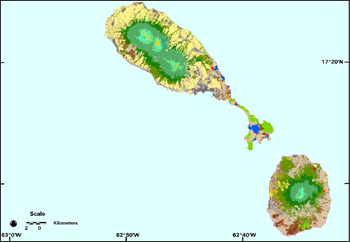

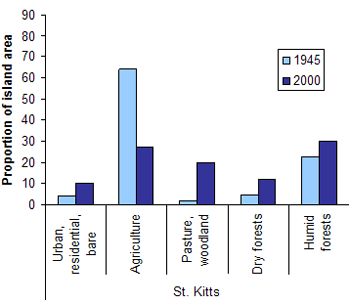

Using these new maps, scientists from the USDA Forest Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, The University of the West Indies, The Nature Conservancy, and Colorado State University compared land use in the new maps with estimates made by the British forester and ecologist J. S. Beard during work with the Forestry Division of Trinidad and Tobago in the 1940s. The authors found that land cover in lowland areas has changed dramatically over the second half of the 20th century. Cultivated land areas on the islands declined 60 to 100 percent from about 1945 to 2000. Meanwhile, forest cover increased by 50 to 950%. They concluded that this trend will likely continue on islands where sugar production has dominated in the past, because growing sugar cane for sugar is no longer profitable on Caribbean islands.

The study also concluded that former agricultural lands in lowland areas could provide lands for new reserves of the drier forest types that have re-established in some areas. Even though the new dry forests are secondary forests, they are important to conserve, because dry forests are greatly underrepresented in the islands’ reserve systems. The land-use history of these islands provides insight for countries that, in the current agricultural commodity boom, are currently clearing vast tracts of old-growth tropical forests for agriculture, possibly not recognizing that eventually such commodities can become unprofitable with supply or demand changes. Insights from the Caribbean sugar cane experience might encourage these countries to hedge against a future collapse of commodity agriculture with a network of the ancient forest reserves. Interestingly, these islands now have the potential to sequester substantial carbon as forest regrowth continues; however, there is also a potential for once again growing sugar cane if the demand for ethanol increases.

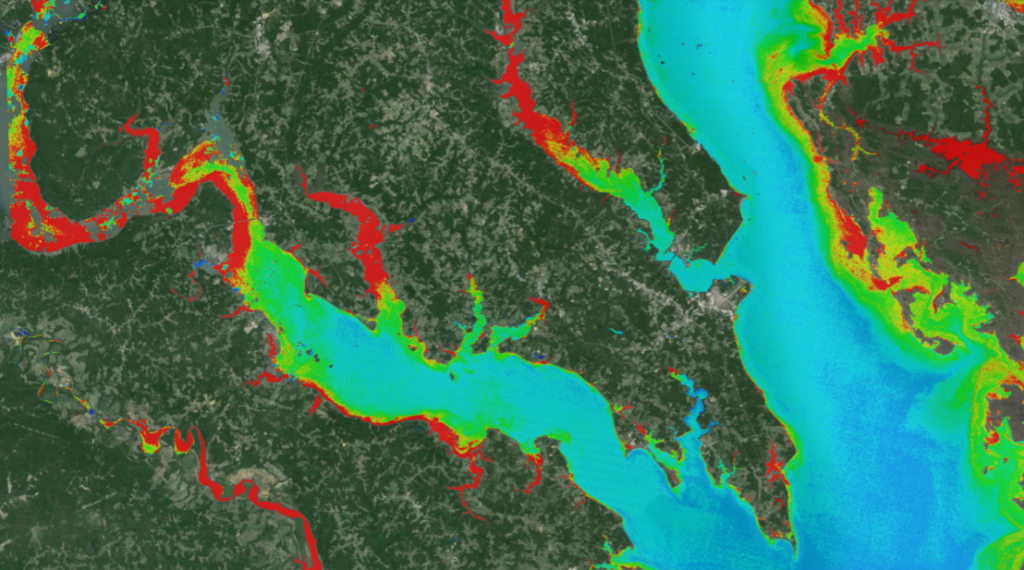

Mapping tropical forest types, and monitoring changes in land cover, are vital to conservation planning. Until recently, however, mapping the vegetation of tropical islands required hand delineation of imagery or aerial photos. One reason is that the forest types change rapidly over short distances on Caribbean islands, from desert-like woodlands where cacti are common to ever-wet cloud forests on mountain tops. Instead of manually delineating forest types, the study used machine learning software to identify the different forest types based on both the satellite photos and other data like topography. The machine learning software can uncover the complicated rules that govern where different forest types occur in the landscape, even for those types that appear similar in the imagery.

Another difficulty has been that most satellite imagery over tropical islands with mountains is partly cloudy. To deal with the clouds in imagery, the scientists created cloud-free image mosaics with a special procedure that fills cloudy areas in a base scene with image data from other dates. The imagery is first “regression-tree normalized”, which minimizes the differences between image data from different dates. The study’s approach to creating the maps accurately distinguished several classes that more standard methods would confuse. Scientists in the group previously published similar maps of Puerto Rico, St. Lucia and St. Vincent, and the Grenadines and have just completed maps for the U.S. and British Virgin Islands as well.

References:

Helmer, E.H., T.A. Kennaway, D.H. Pedreros., M.L. Clark, L.L. Tieszen, T.S. Ruzycki, H. Marcano, S.R. Schill, C.M.S. Carrington (2008). Distributions of land cover and forest formations for St. Kitts, Nevis,

St. Eustatius, Grenada and Barbados from satellite imagery. Caribbean Journal of Science vol. 44 no. 2, pp. 175–198.

Helmer, E.H., T.J. Brandeis, A.E. Lugo, and T. Kennaway (2008). Factors influencing spatial pattern in tropical forest clearance and stand age: Implications for carbon storage and species diversity. Journal of Geophysical Research, vol. 113, G02S04.

A Rendezvous with Landsat

NASA outreach specialists led educators through a workshop on accessing and utilizing Landsat data at the annual Earth Educators’ Rendezvous.