By Laura E.P. Rocchio

The cold waters of coastal Maine are well known for their bounty of lobsters. But in recent years, the aquaculture industry has put Maine on the culinary map for a beloved bivalve, too. Nearly 3 million oysters are now harvested annually from Maine’s waters. Between 2003 and 2015, the oyster market in the state boomed from less than $1 million per year to $4.8 million. The demand for Maine oysters is leading aquaculturists to seek new places to expand growing operations. Finding promising aquaculture sites can be a challenge, though; fish and shellfish farms may be successful in one place, but not another.

Now Maine’s seafood farmers may be getting some help from above. In the first study of its kind, researchers from the University of Maine have demonstrated that Landsat 8 satellite data can be used to find locations where oysters farms should thrive.

Finding the Formula

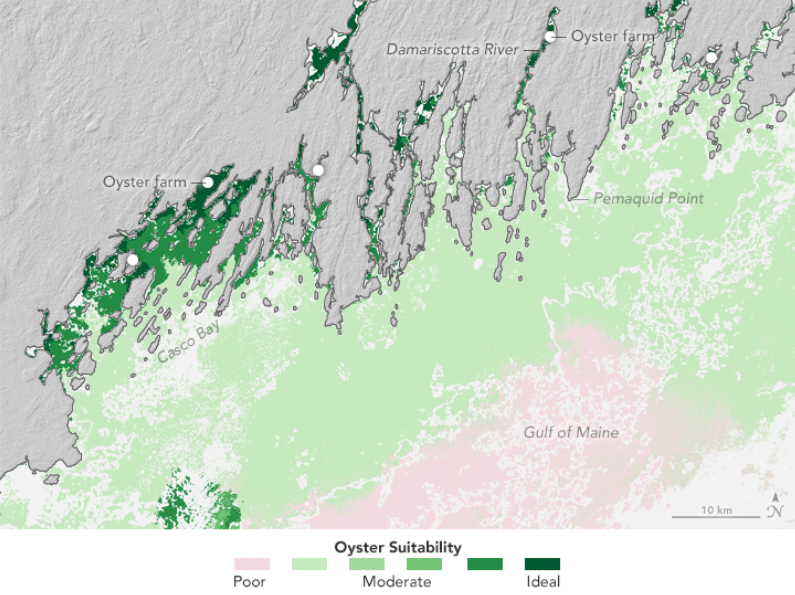

Traditionally, finding new farm locations has been a mix of trial and error; mostly experimentation with new sites within proximity to existing farms. A team of researchers led by Jordan Snyder and Emmanuel Boss of the University of Maine set out to take the costly guesswork out of finding productive sites by creating a Landsat-based map with an “oyster suitability index.”

To create the map, the researchers went back to the basics of oyster physiology. The chief oyster grown in Maine’s waters is the American (or Eastern) oyster, Crassostrea virginica. This filter feeder is different than other oysters because its filtration rate–aka its feeding ability–is strongly influenced by water temperature. The colder the water, the slower the oyster’s filtration speed and the slower it gets the nutrients it needs to grow. They knew they had to find areas with temperate waters on Maine’s chilly coast.

They also considered the amount of food available for the oysters and the amount of non-organic matter floating in the water. Oysters feast on phytoplankton, so they looked at chlorophyll a concentrations; when chlorophyll is abundant in the water, phytoplankton are too. At the same time, high levels of inorganic sediments are not good because the oysters have to filter through a lot of non-food, which slows their feeding down. By measuring turbidity, or suspended sediments in the water, Snyder and Boss could help farmers avoid areas where oysters are more likely to get a mouthful of mud than food.

The team used Landsat 8 data to derive sea surface temperature, chlorophyll a, and turbidity. They then created a formula that could rank the suitability of Maine’s coastal waters for oyster farming. The winning waters—where oysters can grow rapidly—are relatively warm, have high levels of chlorophyll a, and low turbidity.

Oyster suitability maps like the one shown above indicate that existing farms (marked by white circles) are sited in favorable areas. The data also indicate that there are many places along coast where conditions look favorable for new oyster farms. Several oyster farmers are already using the maps. “One farmer is using the chlorophyll imagery to look for places with high food content downeast,” Snyder said. “And [oyster farmer and co-author] Carter Newell is using the index in a flow model to look at new places for farming in the Damariscotta River.”

A Uniquely Suited Prospector

Landsat 8 is uniquely suited for this investigation because, unlike satellite ocean color instruments, it has a fine enough spatial resolution (pixel size) to make measurements in the nooks and crannies of Maine’s coast. Maine has about 3,500 miles of tidal shoreline, and its jagged coast is a series of fjards—the shallow, broad cousins of fjords. It is in the upper reaches of those fjords that oyster farming is most promising.

The researchers made use of Landsat 8’s visible, near-infrared, shortwave infrared, and thermal infrared measurements. The thermal measurements were especially critical for monitoring seasonal water temperature trends. And Landsat 8’s new coastal/aerosol or “true blue” band was critical for the atmospheric correction technique Snyder’s team used and which was required before accurate turbidity and chlorophyll a measurements could be made. (The “true blue” band and Landsat 8’s second blue band were used alternatively in the chlorophyll a calculations depending on which band showed the highest reflectance / greatest signal.)

The researchers validated their index in the Damariscotta River Estuary, site of about three quarters of Maine’s oyster operations are currently in this 18-mile long estuary—companies such as Pemaquid, Glidden Point, Otter Cove, and Hog Island. They found that temperature and turbidity measurements derived from Landsat data matched well with monitoring buoys in the water. The chlorophyll a measurements, while within expectations, were not as good as the team had hoped, but Snyder and Boss have some ideas about how those measurements could be refined. They also think the index could be further developed for other bivalve species and for marine environments outside of Maine.

Getting to Know Maine’s Oysters

The American oyster ranges the North American coast from the Gulf of Mexico up to Canada’s St. Lawrence River. Early Maine inhabitants ate oysters (for some ~5000 years) as evidenced by the shell piles, called middens, left behind that are 30 feet deep in some locations. But the pollution that came along with logging, brickyards and sawmills of European settlers put an end to the fragile Maine oyster ecosystem.

In 1972—the same year the first Landsat launched—a professor from the University of Maine began to research oyster cultivation in Maine, his group starting with a European oyster species, but a parasite decimated that oyster stock in the following decade. So the professor’s group revisited the idea of growing the native American oyster.

Today there are approximately 50 oyster farms that lease watery plots along the coast where they mainly grow American oysters. Maine’s aquaculture industry is made up of small-scale, family-run operations.

Maine waters are too cold for most oysters to spawn (although this is slowly changing with warming waters), so growers typically buy oyster “seed” and once they reach the size of a quarter, the “spat” are then put on the water’s bottom to grow until the reach market size; this takes about three years.

Oyster connoisseurs will argue that this slow growth gives the oysters more time to develop their distinctive flavor—and many say the best time to eat Maine oysters is in the fall when they are plump with stockpiled glycogen for winter.

In the Field

On the Plate

Nearly 3 million oysters are now harvested annually from Maine’s waters. Between 2003 and 2015, the oyster market in the state boomed from less than $1 million per year to $4.8 million. The demand for Maine oysters is leading aquaculturists to seek new places to expand growing operations.

“The OSI could be adjusted for use in other places along the east coast of the USA where Eastern Oysters are grown, such as New Hampshire and Massachusetts,” Snyder postulated, “Or in estuaries that are being monitored for water quality, such as the Chesapeake and Delaware Bays.”

OSI maps are available for download at www.umaine.edu/coastalsat.

References :

Snyder J, Boss E, Weatherbee R, Thomas AC, Brady D and Newell C (2017) Oyster Aquaculture Site Selection Using Landsat 8-Derived Sea Surface Temperature, Turbidity, and Chlorophyll a. Front. Mar. Sci. 4:190. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00190

Maine Sea Grant (2017) Maine Seafood Guide: Oysters. Accessed August 17, 2017.

Maine Sea Grant (2017) The Oyster Trail of Maine. Accessed August 17, 2017.

Maine Boats, Harbors & Homes, via Maine Sea Grant (2008) Maine Oyster Cult. Accessed August 17, 2017.

Maine Food and Lifestyle, via Maine Sea Grant (2008) Maine’s Oyster Renaissance. Accessed August 17, 2017.

Maine Boats, Harbors & Homes (2017) Resilient Shellfish. Accessed August 17, 2017.

University of Maine (2017) High-Resolution Satellite Imagery of Coastal Maine. Accessed August 17, 2017.

Related Reading:

+ Oyster Prospecting with Landsat 8, NASA Earth Observatory