The two burns exhausted the satellite’s fuel for any more burns with the exception of the final burns to deorbit the satellite. The maneuver to reposition Landsat 7 for its 20th and final time executed exactly as intended.

The thruster burns were part of a necessary routine to ensure that the satellite always crosses the equator at 10 a.m. plus-or-minus 15 minutes local time as it orbits from the North Pole to the South Pole. Scientists want the sun’s angle on the landscape they’re studying to be the same image to image, month to month, year to year. So it’s important that Landsat 7 crosses a given point on the globe at roughly the same time each time.

This maneuver, called an inclination maneuver, pushes the satellite toward its outermost boundary of 10:15 local time. The spacecraft will hit a peak of 10:14:55 on or about August 11, 2017, before it begins to drift back reaching its 9:45 threshold by early 2020.

If Landsat 7 is still healthy, its science mission will continue until it reaches 9:15 in mid-2021. The goal is to maintain Landsat 7 science operations for as long as possible—i.e., until a month or two before the Landsat 9 launch, planned for late 2020. This would allow the 8-day repeat coverage of the Earth by the Landsat constellation to continue with only a short interruption while Landsat 7’s orbit is lowered so that Landsat 9 can take its place.

Landsat 7 will likely move to a lower altitude one to two months before Landsat 9 launches to allow Landsat 9 to take Landsat 7’s orbital place at 438 miles above Earth. At that lower altitude, Landsat 7 will not provide science data, and Landsat 8 will likely be the sole provider of Landsat science data while Landsat 9 progresses through its on-orbit test and checkout.

Pushing the Landsat 7 threshold to 9:15 gives Landsat 9 until the middle of 2021 to launch. Beyond that, the Landsat 7 spacecraft’s science data will no longer be valid and its science mission will likely end.

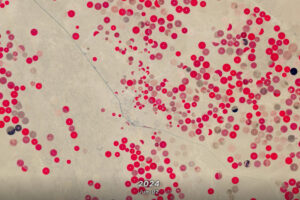

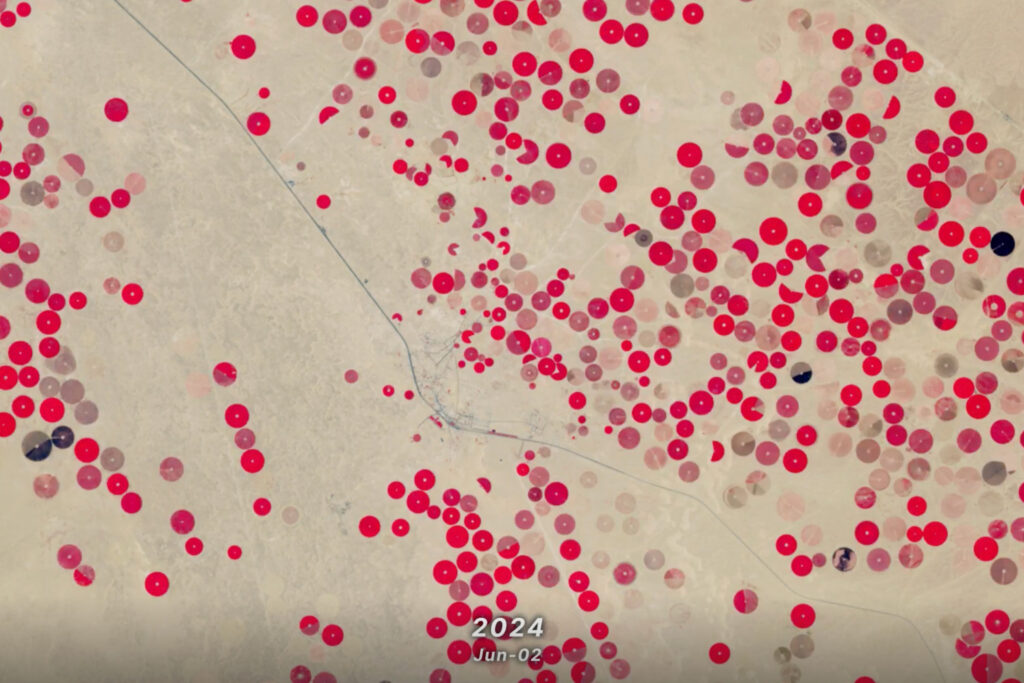

Saudi Arabia’s Desert Agriculture

In this animation of 2024 and January 2025, crop fields in Saudi Arabia cycle through their growing seasons.