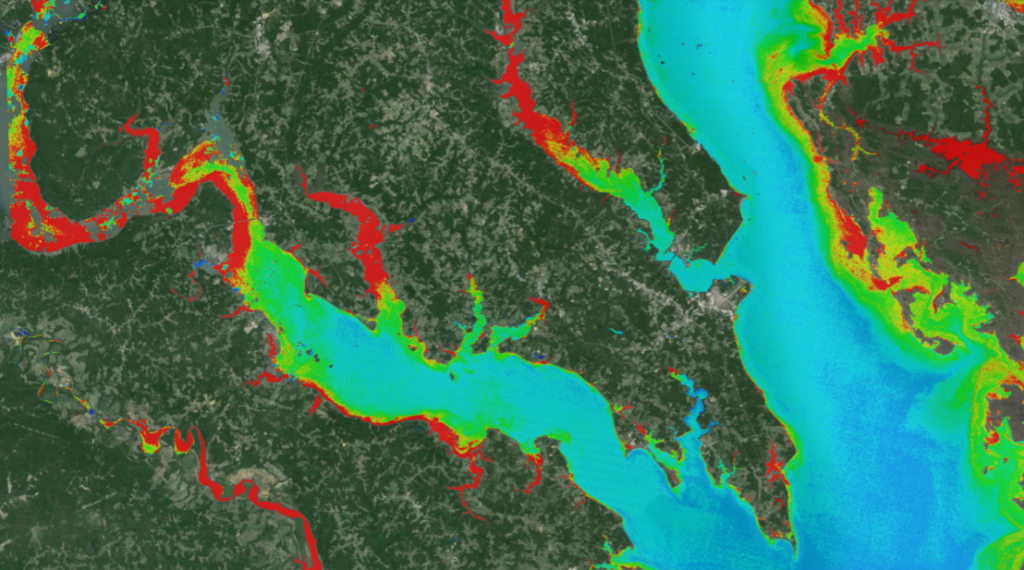

Researchers at North Carolina State University have developed an automated technique that uses satellite imagery to determine when swine waste lagoons were constructed, allowing researchers to determine the extent to which these facilities may have affected environmental quality.

Swine waste lagoons are outdoor basins used to store liquid manure produced by swine farming operations.

“Historically, we only knew how many pigs were found on farms as an aggregate for each county, and that data was only reported to USDA every five years,” says Lise Montefiore, lead author of a paper on the work and a postdoctoral researcher at NC State. “Within the past 20 to 30 years, permitting requirements were established that allow us to determine where swine farms and waste lagoons are located.

“However, we didn’t know when these lagoons were built, making it difficult for us to understand the impact the lagoons had on water quality, air quality and so on. Our work here gives us specific data on when each lagoon was constructed. By comparing this information with historical environmental monitoring data, we can get a much better understanding of how the lagoons have affected the environment.”

“While we focused on North Carolina, this technique could be used to establish lagoon construction dates for any area where we have location data for swine waste lagoons and historical satellite images,” says Natalie Nelson, corresponding author of the paper and an assistant professor of biological and agricultural engineering at NC State.

The researchers started the project with location data on 3,405 swine waste lagoons.

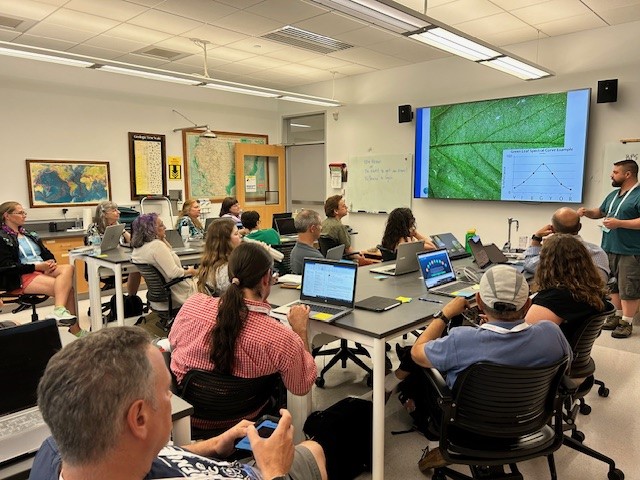

The researchers then collected publicly available satellite images, taken between 1984 and 2012, of the areas where the waste lagoons are located. To determine when each lagoon was constructed, the researchers automated a piece of software to assess the extent to which light reflected off the lagoon’s location. Because lagoons are watery, they reflect light differently than dry land. So, when the reflectance at a site switched from “dry” to “wet,” they knew that a lagoon had been built.

“We found that approximately 16% of the lagoons were already in place before 1987, so there is no exact construction date for those facilities,” Montefiore says. “However, we were able to establish the construction date for the remaining lagoons with a margin of error of about one year.”

“At this point, our goal is to share this data with the broader research community so that we can begin to understand how the construction of these facilities may correlate to changes in air quality, water quality or other environmental variables.”

“This is also the first time that we’ve had this level of historical and geographic detail in terms of understanding how animal agriculture has expanded in North Carolina,” Nelson says. “That can help us understand changes to the landscape and changes to land use over the past 40 years.”

The paper, “Reconstructing the historical expansion of industrial swine production from Landsat imagery,” is published open access in the journal Scientific Reports. The paper was co-authored by Mahmoud Sharara, an assistant professor of biological and agricultural engineering at NC State, and by Amanda Dean, a former undergraduate at NC State.

The work was done with support from North Carolina Sea Grant under award number NA18OAR4170069; the Water Resources Research Institute; the Gulf Research Program of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, under grant 2019-67032-29074 and Hatch Projects 1016068 and 1022103; and a U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Center graduate fellowship awarded to Montefiore.