MoMA has included Laaaaaaandsat in its recent Aerial Imagery in Print, 1860 to Today exhibition. The show is scheduled to close on Sept. 11, 2016. We recently spoke with James Bridle about his art and his use of Landsat imagery:

How did the idea for Laaaaaaandsat come about?

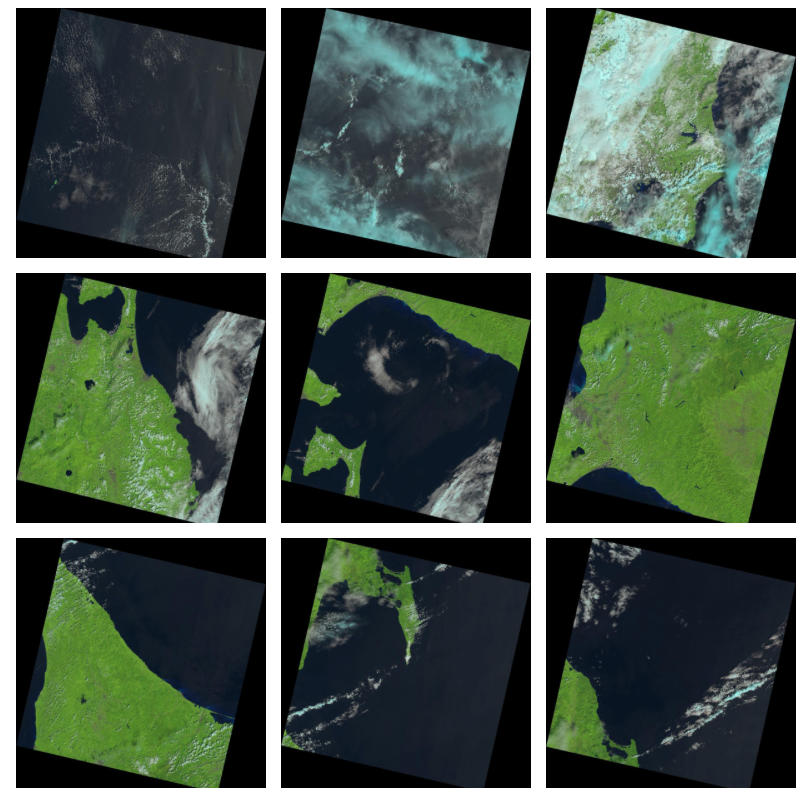

I’ve been working with satellite imagery in my art practice for some time; initially in Google Maps, making online artworks such as Rorschmaps which turn satellite images into live kaleidoscopes, and Dronestagram, which used satellite images to explore the hidden—but yet, with a little investigation, startlingly visible—landscape of drone wars, via social media.

As a lot of my work also investigates the technologies which underly and often guide our modern, digital lives, I became fascinated with the way satellite imagery actually functions—and particularly how it functions differently to photography or even to natural human vision. One result of this was the “Rainbow Plane” project, where I reproduced on the ground a 1:1 version of what I call a “rainbow plane” – the beautiful and fascinating optical effect produced by a plane in flight being captured by the fast-moving sensor of an imaging satellite. Something in this artefact seemed to capture for me the strange and compelling disjunct between the way we see the world, and the way it is viewed through the lens of our technologies. I’ve also undertaken several projects using GPS satellites, such as the sculptures captured in “You Are Here”—visualisations of the constellation of machines we are all living inside.

As I found myself using Landsat images and other satellite image feeds more and more, I enjoyed the way that the glut of these images mirrored our own image-fixated culture, and the endless flow of images one encounters online. It feels both impossible and also revelatory trying to keep up with this boom of information. And so, as a small gesture of bringing these worlds together and making it possible to experience the beauty and depth of the images in a new way, I made http://laaaaaaandsat.tumblr.com: a tumblr for a satellite (and for all the people and infrastructure that make it possible): a blogging machine.

You straddle the computer science and art worlds. How does this influence your perspective?

I studied computer science and artificial intelligence and then got so fed up with computers that I went to work in the traditional publishing industry, where I could spend more time with books, my first love. But I got frustrated there too, at the artificial limits placed on culture, and our access to and appreciation of it, by the rejection of technology and science as having their own cultural vitality, beauty, and possibility. And so my work became one of bridging the gap between the two worlds, and hopefully bringing new perspectives to both. Technology often makes possible or reveals new aspects of culture, and art allows one to bring new perspectives and narratives to scientific discovery. Both are critically important.

In 2013, you wrote in Aperture Magazine, that “Every one of these [Landsat] images is in the public domain, allowing every one of us to use, benefit from, and marvel at this ever-growing, ever-changing automated portrait of our planet.” How important is it that access to Landsat data is free and open?

I think it’s critically important. Firstly because it allows anyone, scientist or artist or simply curious individual, to make use of this information in whichever ways they deem to be important, whether its analysing climate and ecological data, or many other scientific uses, or illustrating the beauty and strangeness of the planet, or anything else. But it also makes a clear statement about what is, or should be, important to us as a global, human culture: discovery, analysis, investigation, imagination. It says that these things are both central to our society and a public good.

You’ve done some political work about drones and surveillance satellites. Landsat, meanwhile, is in the very different realm of environmental monitoring. What is your thought process about this continuum of satellite technology from military to civilian/environmental?

I’m fascinated by the military histories of nearly all technologies, and remote sensing is certainly in debt to this history. This can be an important springboard to launch civilian science projects, but it can also carry over a dangerous legacy of control and violence. Contemporary warfare and surveillance culture would not be possible without space-based and networked systems, but neither would much governance, humanitarian and ecological work, and the internet itself. In “Dronestagram” I was making an explicit connection between the use of satellite networks both to wage wars, and to give concerned individuals, journalists and governments the opportunity to monitor such activities: the network, in my experience, always cuts both ways. These activities—from secretive military communications to the social media we use every day—run on the same substrate. As Melvin Kranzberg famously stated: “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.” In order to understand it, and thus to achieve the greatest agency for the greatest number, it needs to be accessible and comprehensible to all.

Your Laaaaaaandsat project is now part of MoMa’s Aerial Imagery in Print, 1860 to Today exhibit representing “publications by contemporary artists who incorporate aerial imagery into their work, setting the scene for a second century of elevated viewing.” Going forward, will “elevated viewing” continue to be a theme for you?

The elevated viewpoint is such a powerful metaphor for the way power itself functions in the world, I think I will always be fascinated by it. With “The Right To Flight” project in London a couple of summers ago I flew my own surveillance balloon over the city, and came to understand something of the violence that still feels to me inherent in the power imbalance such a viewpoint provided. In response, I’ve become very interested in how we equalize and respond to issues of surveillance and power—but there are many ways of exploring this, not all of them so bleak. Recently I’ve been looking at sport, which provides a compelling and bounded arena within which to explore these issues—from drones flying over football pitches to the cameras mounted high above the basketball court watching all the players. A seat in the top tier of the stadium can tell you as much, it turns out, as the view from space.

Further information

+ Aerial Imagery in Print, 1860 to Today at MoMA

+ James Bridle’s blog

Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Landsat & LCLUC: Science Meeting Highlights

Outreach specialists from the Landsat Communications and Public Engagement team participated in community engagement efforts at the joint NASA and University of Maryland Land Cover Land Use Change (LCLUC) meeting.