By Laura E.P. Rocchio

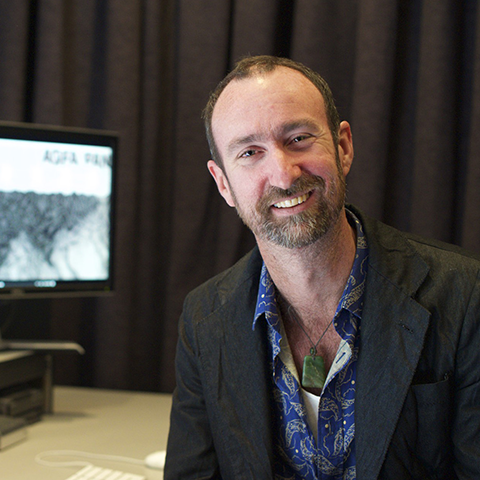

Grayson Cooke

Artist

“Open Air” is a media project of Australia-based artist Grayson Cooke that features Landsat 8 imagery as it explores how time and elemental forces work together to shape our planet.

In “Open Air,” Cooke plays with sense of scale as he focuses on the ever-present Earth system processes that sculpt the landscape by using the juxtaposition of time series Landsat 8 imagery with video from a camera panning slowly over the paintings of Emma Walker, all set to the stripped-down elemental soundscape of The Necks’ “Open” album. Cooke has presented this work at museums, film festivals, and conferences while also making the trailer available online.

We asked Cooke, who is also a professor of media at Southern Cross University in New South Wales, some questions about his “Open Air” project:

What was the inspiration for the “Open Air” project?

I have a long-standing interest in archives and memory, and have recently begun to explore that concept within the context of the environmental archive, the Earth as a repository both of deep-time and anthropogenic time – and of course the widespread current discourse about the Anthropocene shares this concern. A number of my recent projects have explored this idea, and the language and tools of geoscience have provided a great deal of inspiration for me in thinking about how we understand our environment.

Initially I was working on each component of this project separately – filming Emma Walker’s paintings, and talking to Geoscience Australia about the use of Landsat data. At some point I realized that there was a kind of divergent connection between these two projects, the intricately close view of paintings comprised of earth minerals like charcoal and ochre, and the vastly distant view of the Earth itself – and that there would be a really interesting montage effect in bringing these components together.

How did the use of Landsat data for “Open Air” and your collaboration with Geoscience Australia come about?

I had worked with Landsat images on a previous project actually, “This Storm is Called Progress,” which involved time-lapse video of Antarctic ice shelves using images made available by the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado. While I was doing that project, I started to wonder about whether I could bring the process closer to home and produce time-lapse Landsat images of Australia.

Then I discovered Geoscience Australia and the Australian Geoscience Data Cube, now called the Digital Earth Australia program, which stacks 40 years of Landsat imaging of Australia into a single database. This got me terribly excited, of course, and so I contacted them and pitched the idea of working creatively with their archive of Landsat data, and they very kindly facilitated my access to the National Computational Infrastructure and trained me in how to access and process the data.

In “Open Air” you play with sense of scale, the micro and macro view of a changing planet. Why did you decide to use aerial imaging of Emma Walker’s paintings for your micro-scale views?

While I was visiting an exhibition of Emma’s in Sydney, I got the idea that a camera moving slowly over the complex landscapes and topographies of her paintings, which are very Australian in their forms and colours and materials, might actually feel like aerial photography and so could operate as a kind of creative Earth imaging.

A lot of my work involves using motion-control equipment to create these beautifully smooth controlled camera movements, so I approached Emma about this idea and began to experiment both with filming existing paintings, but also filming the processes and materials that go into the paintings’ construction.

How did you choose the Australian locations featured in the Landsat time series sequences?

There were a number of factors behind the main areas I chose to focus on – and in part guided by my contacts at Geoscience Australia, who work with Landsat images every day and who have a strong aesthetic appreciation of them as well as scientific understanding. They all agreed that the more remote parts of Australia tended to produce more interesting satellite images – desert areas with less vegetation, the salt lakes, outback mountain ranges composed of marine sediment.

The concept of this project was to creatively image the forces that shape the Earth, so I also focused on coastal and tropical regions that receive significant precipitation, and on systems like the Channel Country, a vast area of arid flood plains and braided rivulets that essentially pumps tropical rain from the north down towards Kati Thanda – Lake Eyre, the huge salt lake in the centre of the country.

I ended up working just with data from a period of about 14 months, so each time-lapse sequence is really made up of about 20 images which play in a loop. Even so, it’s amazing to watch the change that unfolds over a year in the Channel Country – you really do get insight into the “life” of the country when you can watch the pulsing of tropical rains flooding through these river systems, and the effect on the salt lakes as they fill and dry out, again and again.

What spectral band combinations where used for the Landsat images you featured and how was that decision made?

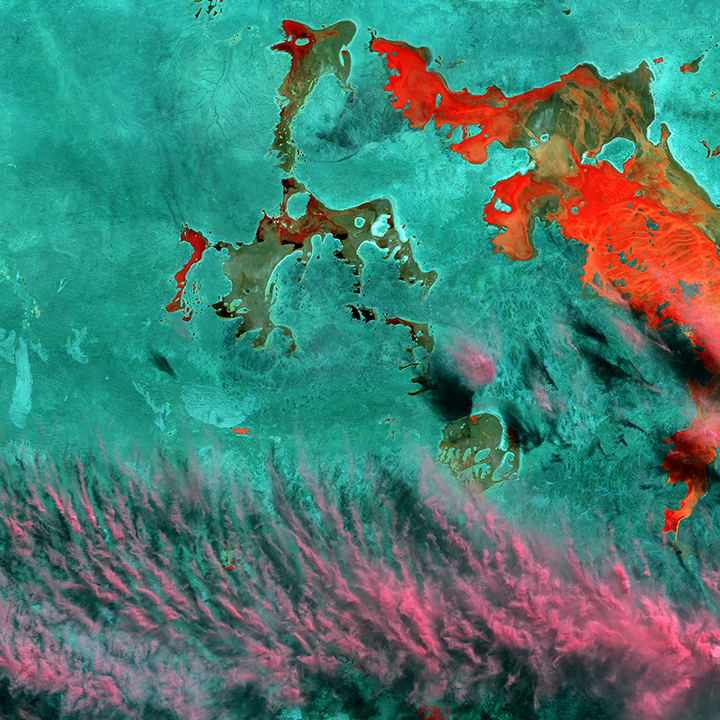

I took a fair bit of creative license with these! Again, my contacts at Geoscience Australia were influential in that they took me through the uses they make of Landsat data for monitoring vegetation and aridity, tidal extent and so on, and thus the different uses they make of false colour mappings and the IR bands. From that lead I simply experimented with different combinations, following aesthetic criteria and also looking for combinations that highlighted the presence and movement of surface water. It was only Landsat 8 I worked with, so a lot of the combinations used the Near Infrared band in combination with red and green or green and blue.

I also made use of the Coastal Aerosol band a lot and band combinations which produced a startlingly surreal world of turquoise earth, red salt lakes and puffy pink clouds. Again, this combination was predominantly sought for aesthetic effect, but I found that there was a value in pursuing these images that were so far from what we normally think of as “the Earth from space” – the strangeness in the image as it unfolds keeps it from resolving into documentary truth, it maintains its potential for both intellectual and affective engagement.

Near the end of “Open Air” you focus on cloud formations. What was the intent of those sequences?

Yes – in the trailer online we see a sequence that is primarily clouds, and in the full work (which is over an hour in length), there are extended sequences that highlight cloud formations. From having worked early on with the USGS LandsatLook application, which has a cloud-filter option, and also speaking to geoscientists who use Landsat data, there is obviously a need for cloud-avoidance because clouds obscure the view of the land. Because “Open Air” is about exploring phenomena over time, including atmospheric phenomena that are intricately connected to the shaping of the Earth, I needed to take the opposite approach and include as much cloud as possible!

For me, this is the value of being able to approach the Landsat program in an artistic and open-ended fashion; as I gathered more materials and explored more parts of the country, and of course experimented with some quite surreal spectral band combinations, the enormous variety and beauty of cloud formations that spread over the country came into stark relief, and I realized I had to build them into the project as an “environment” all of their own.

Your current research focus is on media art and the archive. Was the historic nature of the Landsat data archive of particular interest to you?

Yes – there is in fact a kind of conceptual recursivity to Landsat and the notion of the archive that I find particularly resonant. We now have over 40 years of Landsat data, that represents a phenomenal archive of information about environmental change on Earth, anthropogenic and otherwise. And, the fact that USGS and NASA makes this archive freely available, seems to me to be an inestimable service to the world, and the research community in particular.

In the book Archive Fever, author Jacques Derrida emphasizes the value of the openness of the archive: “Effective democratization can always be measured by this essential criterion: the participation in and the access to the archive, its constitution, and its interpretation.” Because I am interested in archives as resources for personal, national and international knowledge, memory and identity, and the ways that archives are accessed, the Landsat archive strikes me as a really interesting and immensely valuable phenomenon.

But there is an archive within the archive, because Landsat imaging proposes the Earth itself as an archive: it tracks environmental change over time, it demonstrates the degree to which the Earth records its past, and it tracks over landforms that are in turn archives of immense period of time. This project only makes visible environmental change over 14 months, but it explores phenomena that have shaped this continent for millions of years.

Did you know immediately that you wanted to use the stripped-down, elemental sound of The Necks’ “Open” album for the “Open Air” soundtrack or was there a protracted search for appropriate music?

Emma is a friend of The Necks and has produced album art for them over the years, so she was keen to see if we could use their music in some way. The use of “Open” emerged almost accidentally though – I was editing together some early screen-tests of footage shot in the studio, and was casting round for some music to edit it to.

I chose “Open” pretty much on a whim – and it was only after working with it for awhile, and listening to the album as a whole, that I realized the immensity of the work and how well it would fit with both components of the project. Emma is a friend of The Necks and has produced album art for them over the years, so she was keen to see if we could use their music in some way.

The use of “Open” emerged almost accidentally though – I was editing together some early screen-tests of footage shot in the studio, and was casting round for some music to edit it to. I chose “Open” pretty much on a whim – and it was only after working with it for awhile, and listening to the album as a whole, that I realized the immensity of the work and how well it would fit with both components of the project.

So far, what has the public’s reaction to “Open Air” been?

They loved it

Further Reading:

+ Interview with SCU Media Artist, Professor Grayson Cooke, The Echo [link added Feb. 20, 2019]

+ An artist’s surreal view of Australia – created from satellite data captured 700km above Earth, The Conversation [link added Oct. 9, 2018]

+ What did a professor do to attract the attention of NASA? The Northern Star [link added Mar. 13, 2018]

+ An artist’s surreal view of Australia – created from satellite data, Geoscience Australia [link added July. 9, 2024]

Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

*7/11/2024: Updated the last sentence of the 2nd paragraph

to provide locations where Cooke’s Open Air has been presented.