By combining data from Landsat satellites, airplanes and ground-based crews, the researchers have shown in unprecedented detail how insects affect Western forests over decades.

In the past, forest managers relied on airplane surveys to evaluate insect damage over broad areas. However, satellites can reveal patterns at a much finer scale. By combining both types of data, scientists are refining estimates of damage and showing how they may relate to other factors that determine forest structure and composition.

“This is the first time anyone has compared the impacts from these two insects in consistent units of change going all the way back to 1970,” said Garrett Meigs, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Vermont. Meigs conducted his analysis while he was a Ph.D. student in the College of Forestry at Oregon State University. He worked with Robert Kennedy, an expert in landscape analysis and an assistant professor in OSU’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences.

They published their findings in this week’s issue of Forest Ecology and Management, a professional journal.

Outbreaks of both insects occur in cycles and can affect millions of acres of forest lands from year to year. The mountain pine beetle has killed lodgepole pine trees across much of western Canada and the United States in recent decades. Western spruce budworm defoliates – but does not normally kill – Douglas-fir, spruce and true firs. However, repeated years of western spruce budworm attack can weaken trees and make them vulnerable to other stresses, which may eventually kill them.

“Mortality from bark beetles is only the beginning of long-term change,” said Helen Maffei, a U.S. Forest Service scientist in Bend, Oregon, who supported the study. “Dead trees fall and decay, and forest regrowth begins and continues over many decades. This new technique can help us understand not only how insect outbreaks are initiated and spread but also address the question, ‘What comes next’? It can help us better understand the process of recovery.”

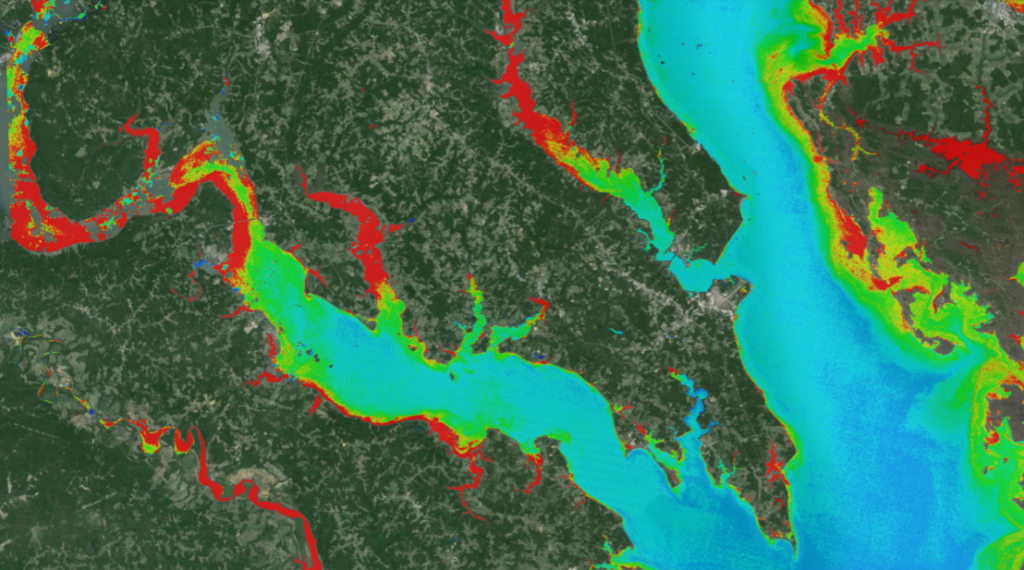

The new method of using Landsat satellites, aerial surveys and forest inventory data enables scientists to identify hotspots of insect activity that may need special attention from forest managers in the future.

“By blending the richness of the Forest Service data with the robustness of the satellite signal, I think we have a really useful new approach to understanding insect patterns on the landscape,” said Kennedy.

The new methods aren’t yet available to businesses, government agencies and other organizations, but through a partnership between Oregon State and Google, that may change. Kennedy is working with the company to use satellite data and new analytical procedures in a system that would be accessible to land managers. The system will be freely available on Google’s Earth Engine, a platform for planetary data and analysis.

“If successful, it would mean that agencies could begin working with the satellite data and potentially take the next step in merging with the Forest Service observation data directly,” said Kennedy.

The report is online in OSU’s Scholar’s Archive, http://hdl.handle.net/1957/55196. Support was provided by the NASA Earth and Space Science Fellowship Program and the USDA Forest Service.

Further Reading:

+ New beetle, budworm maps could help forest managers, The Bulletin

Reference:

Be Part of What’s Next: Emerging Applications of Landsat at AGU24

Anyone making innovative use of Landsat data to meet societal needs today and during coming decades is encouraged to submit and abstract for the upcoming “Emerging Science Applications of Landsat” session at AGU24.