By Madeleine Gregory

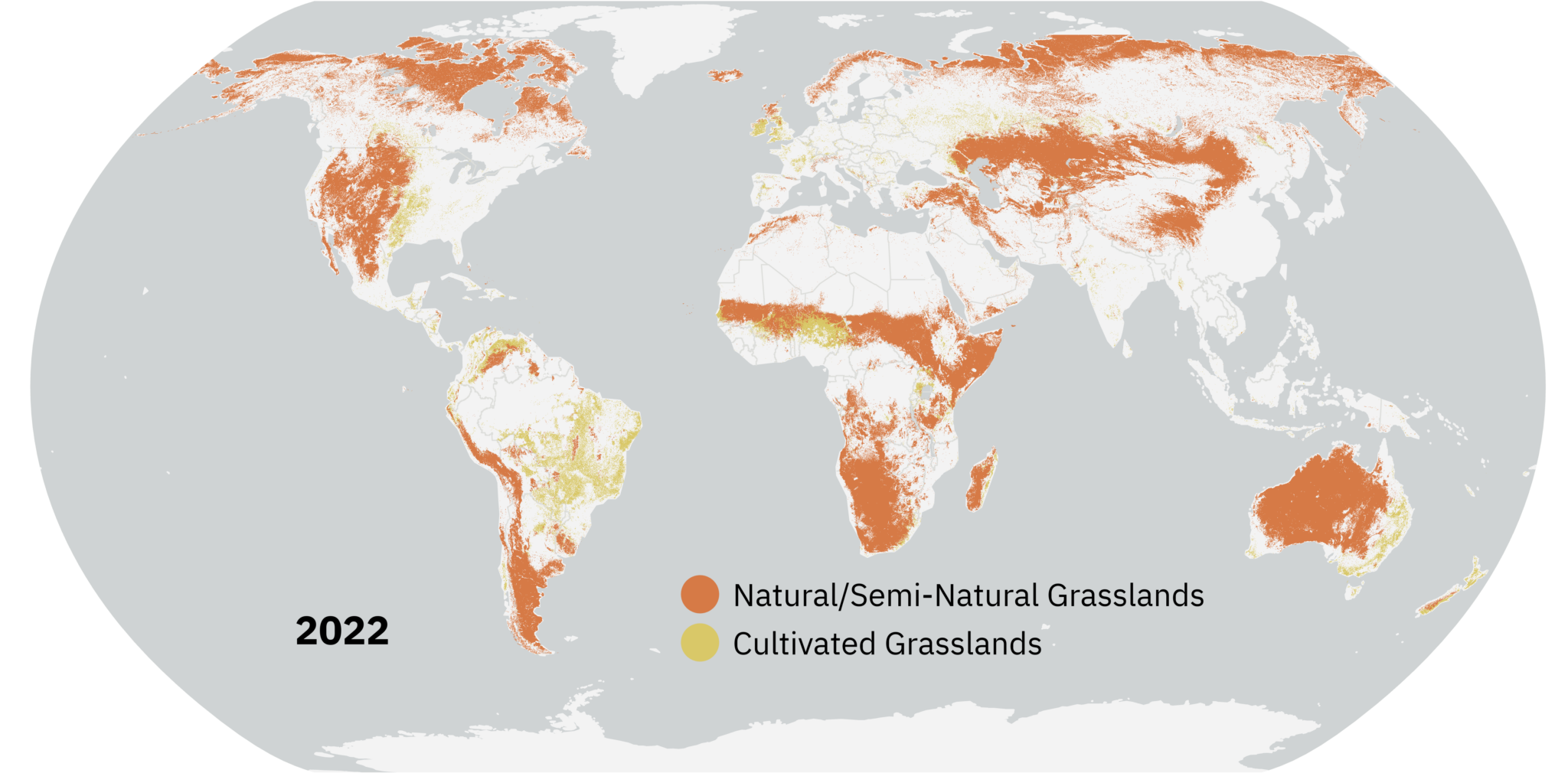

Grasslands tend to get left out of conservation discussions, in which ecosystems like rainforests and tundra take center stage. However, grasslands are the single largest land cover on Earth’s ice-free surface. They store 34% of the world’s terrestrial carbon stock and provide critical habitat to large mammals like elephants. Despite their importance, these ecosystems are often unprotected—less than 5% of temperate grasslands are protected—and easily converted to farmland or otherwise disturbed by humans.

In 2022, Land & Carbon Lab—a partnership between World Resources Institute and the Bezos Earth Fund—convened the Global Pasture Watch research consortium with the hopes of turning the spotlight on grasslands. Using a Landsat-based machine learning model, they created free and publicly available annual maps of grassland extent from 2000-2022, classifying grasslands as natural or cultivated. By analyzing over 20 years of data, the team is now assessing how grasslands across the globe changed over time. Lindsey Sloat, a research associate with Land & Carbon Lab, is part of the Global Pasture Watch team that created these maps. Below, she discusses some takeaways from that research.

What is one major takeaway from your research?

Grasslands are incredibly challenging to monitor at the global scale because they are so heterogeneous—grasslands in the Serengeti look vastly different from those in the American Great Plains or the Mongolian Steppe. This heterogeneity has contributed to a lack of consistent, high-resolution spatial data for grasslands globally. Our work represents a significant step toward filling this gap. People seem to value the contributions we’re making in this space and the open nature of the data, and we’re excited to continue refining and building on these datasets over time.

Why did you use Landsat in this work? Did it give you any insight that would have been difficult to get otherwise?

We used Landsat primarily because of its long time series, which allows us to analyze changes in grasslands over two decades. It’s important to have a decent temporal coverage in order to say something about how these areas are changing. We also had some high impact use cases that required a longer time series, such as using the data for Greenhouse Gas Protocol compliant Land Use Change emissions calculations, which benefit from a 20-year lookback period. Additionally, Landsat’s 30-meter spatial resolution strikes a balance – it’s detailed enough to provide actionable insights for local and regional decision-making, yet broad enough to enable global-scale analyses. This level of granularity helps us capture fine-scale dynamics, such as grassland fragmentation, that would be missed by coarser datasets.

Why is medium-resolution grassland monitoring important?

Medium-resolution grassland monitoring is critical because these landscapes are central to numerous global priorities. Grasslands support biodiversity, provide livelihoods through livestock grazing, act as carbon sinks, and play a role in water regulation. We want the maps we’re creating to serve multiple use cases, including:

- Land-use planning and management: Helping policymakers and stakeholders make informed decisions about how to allocate and preserve grassland areas.

- Supply chain monitoring: Supporting sustainable sourcing efforts by tracking conversion of natural ecosystems.

- Carbon accounting: Contributing to accurate reporting of greenhouse gas emissions and carbon sequestration from grasslands.

- Restoration planning: Identifying degraded areas suitable for restoration efforts.

- Finance for sustainable agriculture and nature-based solutions: Providing data for assessing the impacts and benefits of investments.

Are there any research questions you’re interested in that build off of this work?

Yes! We have several complementary datasets in development that will provide insights into the management, condition, and productivity of grasslands. We would like to combine several of these together into a more finely resolved legend that can say more about grasslands as a land cover and a land use. These data are also being integrated into an ensemble land cover product with other classes. Our ultimate goal is to create datasets that are broadly usable, openly accessible, and adaptable to different local and global contexts. We see this work as just the beginning of a broader effort to improve the monitoring and management of grasslands worldwide, hopefully through continued collaboration and great partnerships.

First author:

Leandro L Parente

OpenGeoHub Foundation

Co-authors:

Lindsey Sloat

World Resources Institute

Davide Consoli

OpenGeoHub Foundation

Nathália Teles

UFG Federal University of Goiás

Maria O Hunter

UFG Federal University of Goiás

Steffen Ehrmann

German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv)

Ziga Malek

IIASA International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

Ana Reboredo Segovia

World Resources Institute

Fred Stolle

World Resources Institute

Steffen Fritz

IIASA International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

Vinícius Vieira Vieira Mesquita

UFG Federal University of Goiás

Radost Stanimirova

World Resources Institute

Carmello Bonannella

OpenGeoHub Foundation

Ana Matos

UFG Federal University of Goiás, LAPIG – Remote Sensing and GIS Lab

Ivelina Georgieva

IIASA International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

Carsten Meyer

German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv)

Icshani Wheeler

OpenGeoHub Foundation

Tomislav Hengl

OpenGeoHub Foundation

Laerte Guimaraes Ferreira

UFG Federal University of Goiás

Parente, L.; Sloat, L.; Mesquita, V.; Consoli, D.; Stanimirova, R.; Hengl, T.; Bonannella, C.; Teles, N.; Wheeler, I.; Ehrmann, S.; Hunter, M.; Ferreira, L.; Mattos, A. P.; Oliveira, B.; Meyer, C.; Şahin, M.; Witjes, M.; Fritz, S.; Malek, Ž.; Stolle, F. Annual 30-m Maps of Global Grassland Class and Extent (2000–2022) Based on Spatiotemporal Machine Learning. Scientific Data 11 no. 1 (2024). 1-22 https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4514820/v3.