Source: University of Northern British Columbia (This story was originally published by UNBC on Jan. 15, 2019)

Alpine glaciers have existed in North America for thousands of years. They represent important, frozen reservoirs for rivers – providing cool, plentiful water during hot, dry summers or during times of prolonged drought.

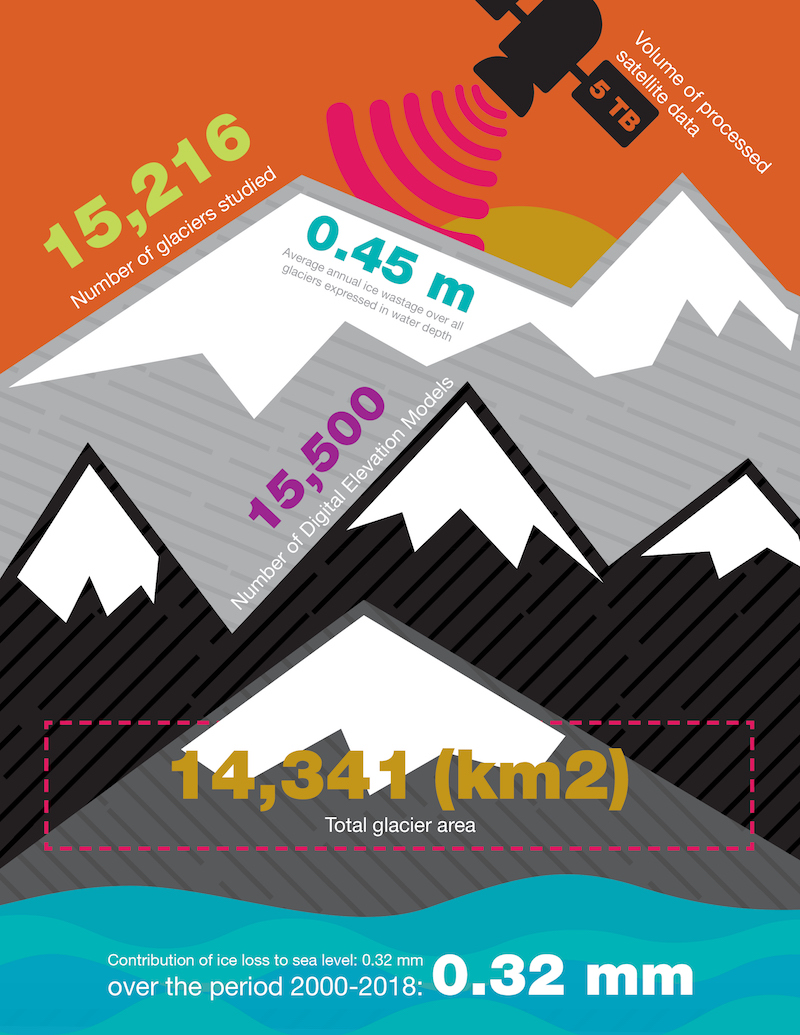

Glaciers are faithful indicators of climate change since they shrink and grow in response to changes in precipitation and temperature. The first comprehensive assessment of glacier mass loss for all regions in western North America (excluding Alaskan glaciers) suggests that ice masses throughout western North America are in significant decline: glaciers have been losing mass during the first two decades of the 21st century.

Their findings, entitled “Heterogeneous changes in western North America glaciers linked to decadal variability in zonal wind strength,” has been published today in Geophysical Research Letters.

The research team included scientists at the University of Northern British Columbia (UNBC), the University of Washington, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Ohio State University and the Université de Toulouse in France.

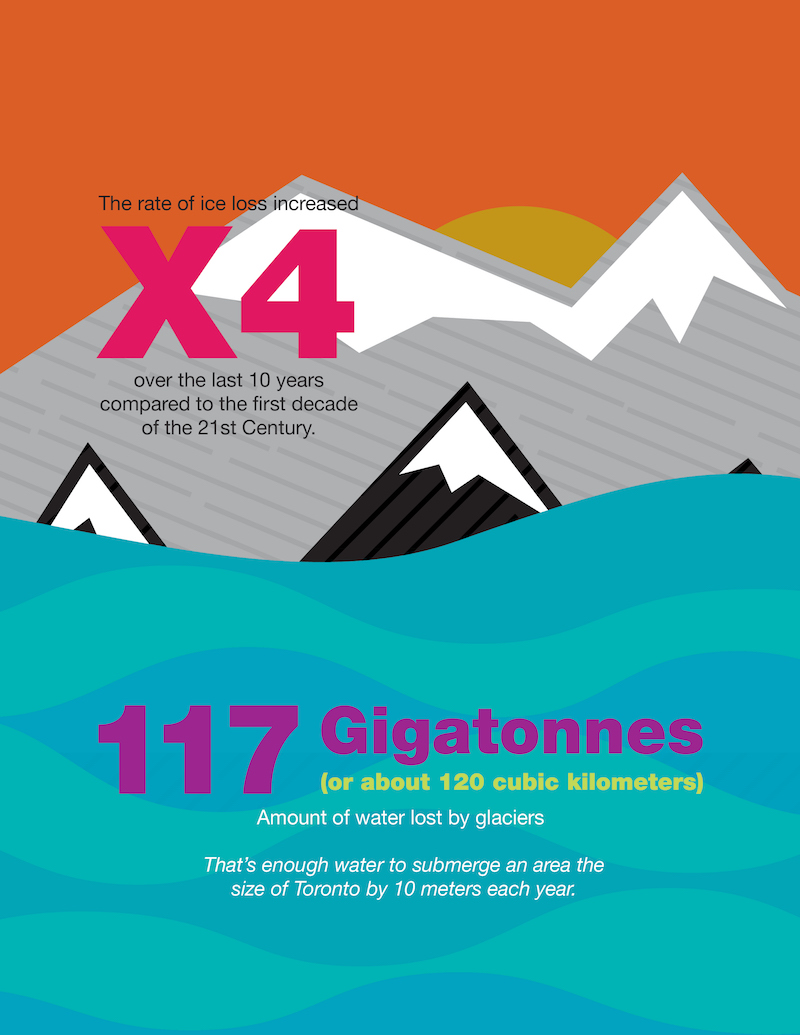

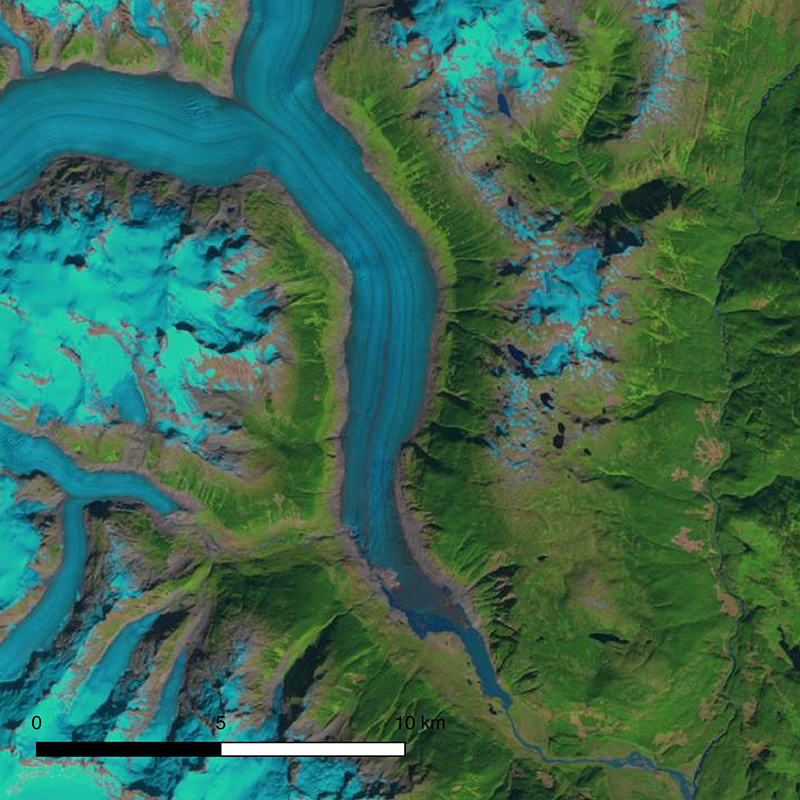

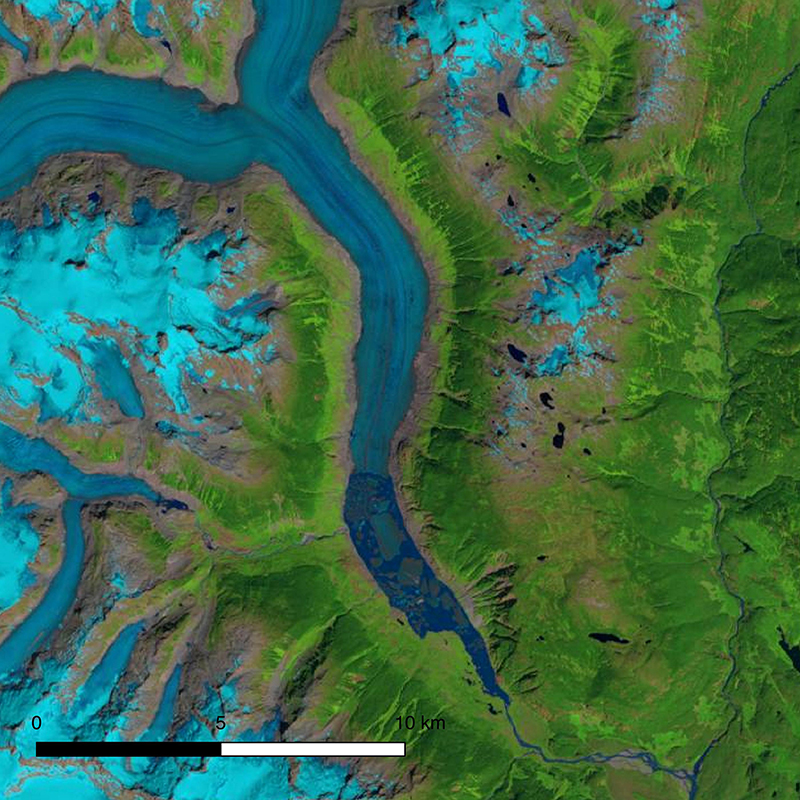

The research team used archives of high-resolution satellite imagery to create over 15,000 digital elevation models covering glaciers from California to the Yukon. These elevation models were then used to estimate total glacier mass change over the period of study. Over the period 2000 – 2018, glaciers in western North America lost 117 Gigatonnes of water or about 120 cubic kilometres – enough water to submerge an area the size of Toronto by 10 meters each year. Compared to the first decade of the 21st Century, the rate of ice loss increased fourfold over the last 10 years.

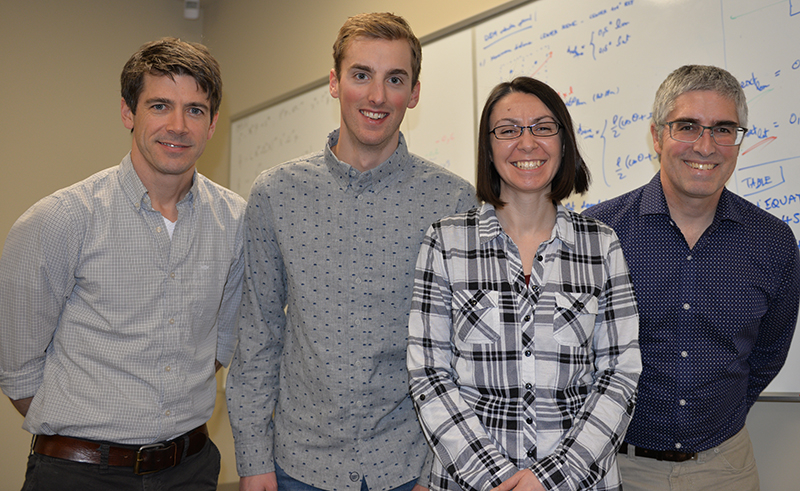

UNBC’s team involved in the study include Dr. Brian Menounos, a professor of Geography and Canada Research Chair in Glacier Change; Assistant Geography Professor Dr. Joseph Shea, and two PhD students Ben Pelto and Christina Tennant.

“Our work provides a detailed picture of the current health of glaciers and ice outside of Alaska than what we’ve ever had before,” said Menounos, the lead author of the paper. “We determined that mass loss dramatically increased in the last 10 years in British Columbia’s southern and central Coast mountains, due in part to the position of the jet stream being located south of the US-Canada border.”

The jet stream is an area of fast flowing upper winds that can steer weather systems over mountains and nourish glaciers with precipitation, mostly in the form of snow that builds up over time and later becomes ice.

“Frequent visitors to America’s glacierized National Parks can attest to the ongoing glacier thinning and retreat in recent decades. We can now precisely measure that glacier loss, providing a better understanding of downstream impacts,” said co-author Dr. David Shean of the University of Washington. “It’s also fascinating to see how the glaciers responded to different amounts of precipitation from one decade to the next, on top of the long-term loss.”