An Accidental Activist

In the summer of 2005, Rebecca Moore came home from her job as an engineering manager at Google and found a legal notice in her mail that notified local residents about the San Jose Water Company’s plan to harvest timber in their community, which is part of the Los Gatos Creek Watershed.

The notice included a map that didn’t make sense to Moore, who describes herself as a “map geek.” After studying the map without much success, Moore decided to plug the information into Google Earth, which had been released two months earlier and was still somewhat of a novelty. Moore punched data from the map into the program, and added information on the location of local schools and landmarks.

“It was going to be more than 1,000 acres of redwood trees that they were going to cut, and they thought they could get away with getting very sketchy information to the community and just railroading the approval process.”

At a meeting where Moore showed 300 members of her community what the proposal entailed, people gasped when they realized what was really at stake.

“The plan was 400 pages; no one reads that – here you see it in seconds,” Moore said, pointing to the image on her laptop screen.

After a protracted two-year battle, Moore and her compatriots were able to stop the logging by proving that the company’s plan posed significant environmental dangers, and was ultimately illegal.

Saving the Amazon Rainforest ( . . . with Google?)

While Moore was using Google Earth in California, Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans and first responders were using the program to coordinate rescue operations. “We got a phone call from the Coast Guard saying that using Google Earth they saved more than 4,000 people,” said Moore. “I think that surprised the Google execs – maybe this is not just a toy, maybe it’s not just this recreational tool for exploring where to go on vacation. Maybe it actually has a more powerful social benefit.”

Moore convinced the execs at Google to let her spend one day a week acting as a liaison with environmental groups and teaching them how to use Google’s mapping tools. At the time, Google had a program that allowed employees to volunteer for such efforts. Moore’s project was called Google Earth Outreach (GEO).

Almir discovered Google Earth while visiting an Internet cafe.

“My people are not prepared to defend ourselves unless it’s with bows and arrows, but those won’t work anymore,” Almir said in a video documenting their work. “We needed to get prepared and create a dialogue with a society that is not ours. I realized the need to use Internet technology as a tool to make my people’s situation known.”

Moore and her team set up a training program in Rondonia. Many of Almir’s people had never even used a computer, so they were taught the basics of Google Earth. Tribal youth were trained on how to use digital photos and YouTube to tell stories, which were uploaded to a Google Earth map of the region.

Once the mapping project was complete, the Pater Surui wanted to continue their efforts to fight logging. Moore and her team returned to the region in 2009 and trained the tribe to use smartphones equipped with software that would allow them to collect data from the forest and submit the data to Google Earth.

Vasco Van Roosmalen, director of ACT, explained, “The Surui use [the data] to monitor their biodiversity, to monitor their borders, and also to monitor their forest in the context of climate change.” The tribe is able to measure how much carbon they are preventing from going into the atmosphere by maintaining the forest and replanting with new saplings. The Pater Surui have an ambitious plan to plant 100 million saplings by the end of 2019 in an effort to reforest the region.

The Pater Surui are using the data they collect to trade carbon credits in a carbon marketplace. In September 2013, Ecosystems Marketplace reported that a Brazilian cosmetics company, Natura, purchased 120,000 tons of carbon offsets from the tribe, making the Pater Surui the “first indigenous people to generate credits by saving endangered rainforest.”

66,000 Computers and Erasing Clouds

While Moore and her team were there with Almir, she was approached by Carlos Souza Jr., a Brazilian geoscientist from Imazon. Souza was looking for a way to quickly and efficiently process the satellite data used to observe and prevent illegal logging in the forest where they were losing more than 1 million acres of rainforest each year. He asked Moore if Google could create a technology that would allow researchers to analyze the data.

It took Moore and her team three years, but they were able to design the Google Earth Engine, a platform that could process copious amounts of data for Imazon’s Deforestation Alert System in a timeframe that would allow Souza and his colleagues to see illegal logging from the satellite data, send people out into the field to confirm, and then notify the authorities. According to Imazon, they were able to reduce illegal logging by 97 percent between 2007 and 2010 in Paragominas, an area where deforestation was happening on a large scale.

“There are all these NASA satellites up there right now collecting incredibly useful data. The Landsat instrument is collecting 600 images a day – there’s more than 4 million images over 40 years,” said Moore.

She and her team realized that if they could figure out how to efficiently process this data, they would be able to open a floodgate of information for important science and Earth observation. Up until this point, these data were expensive, but in 2008 the U.S. government made all of the Landsat data free. They took this treasure trove of data that the U.S. Geological Survey was storing on tapes in a secure archive in South Dakota and put it online in Google data centers.

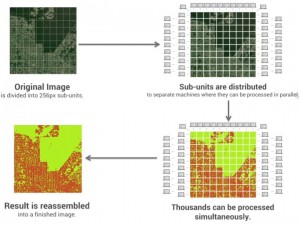

Once the data was free, scientists could access it, but how do you process so much information?

They had over 30 years of images, totaling 909 terabytes of satellite data. (When Computer Weekly set out to provide a tangible comparison of what a petabyte would look like for the layperson, answers included “enough to store the DNA of the entire population of the U.S. – and then clone them, twice.”)

For each spot on the planet, they used Google Earth Engine to sift through all the images and find the best pixel for each point, and reassemble the pixels to create clear, cloud-free images. “This would have taken like 300 years, but we did it in one and a half days,” Moore explained gleefully.

Google Earth Engine, in partnership with Time magazine, used these cloud-free images to create timelapse videos of Brazilian deforestation, glacial retreat, and urban expansion.

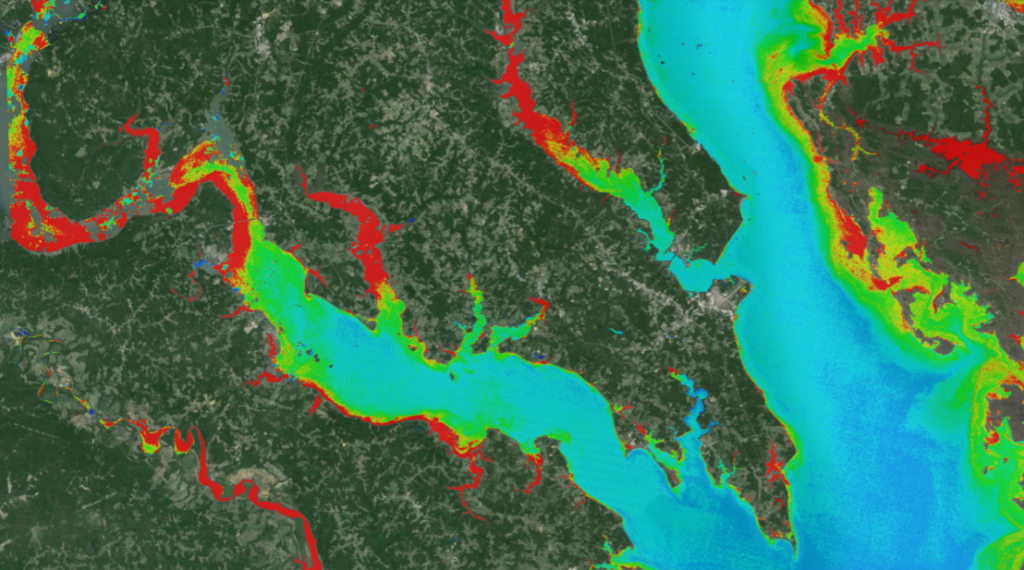

Moore is beyond enthusiastic about the potential for Earth observation and science that this platform makes possible. She pulls up image after image on her computer to show what kinds of observations are possible – from precision agriculture and drought monitoring to predicting hazards that emerge when conditions are ripe for mosquito hatches, a common disease vector.

“We have really hit a sweet spot with the geoscience community,” she said at a Google conference in 2014. “Can we make remote sensing – this type of Earth observation data analysis – transformative or disruptively easier than it’s been before, so you don’t have to be a Ph.D. in that field in order to come in with new ideas to contribute something new to this community and to this space and maybe transform the world in a way that nobody has ever anticipated before?”

Further information:

+ How a Google Engineer, 66,000 Computers, and a Brazilian Tribe Made a Difference in How We View the Earth, Earthzine

+ Maps for Good: Saving Trees and Saving Lives with Petapixel-Scale Computing

+ Timelapse, Time Magazine