Back on shore, their families farm the land—called mashamba—high into the hills, growing staples like cassava, beans and maize. Occasionally, the mashamba are on slopes so steep that the men, women and children who tend them seem to defy gravity.

This agriculture on steep slopes has, however, led to frequent erosion, flooding and landslides that degrade or completely denude arable land, while also affecting water quality and quantity and likely hindering stocks of edible fish that spawn near the lakeshore. In the most severe cases, these events damage property and take lives in the process. There is a strong memory among local residents of a mudslide several years ago that wiped away a number of houses and other structures and the people they contained in two villages along the lake. These landslides also erode habitat for wildlife, including chimpanzees.

The Jane Goodall Institute (JGI) realized that to address this challenge—for the benefit of people and chimpanzees—they needed a higher vantage point and a look back in time. “We looked at satellite images taken by the NASA-U.S. Geological Survey Landsat missions from 1972 and 1999,” explained Lilian Pintea, vice president of conservation science for JGI, “and the loss of forest and woodland cover along valleys and steep slopes was clear: eighty percent of the forests were gone. Through our analysis of Landsat forest change maps using GIS, we also calculated that the risk of landslide had increased fivefold during that time.”

JGI initiated a forest monitoring program in 2005, training and ultimately equipping community members with GPS-enabled Android smart phones and tablets for capturing observances of forest use and regeneration. The Forest Monitors mark where they see snares for animals, trees that have been cut for timber or firewood, charcoal kilns and other threats, as well as occurrences of chimpanzees and other wildlife. This information helps efforts to reduce illegal activities, monitor changes, and track progress in the landscape over time. It also helps JGI’s crowd-sourcing efforts that combine citizen science with Landsat imagery and ecological modeling. A NASA-funded project has helped enable these connections and innovations.

“We are marrying the latest technologies—using NASA’s data and science—with boots on the ground to improve forest and chimpanzee conservation decisions from village to continental scales,” Pintea explained.

Through a democratic land-use planning process in which every village member has a vote—a process the American people funded through USAID Tanzania—JGI worked with communities to facilitate village land use plans. These plans identified areas where people could build homes, areas for agriculture or livestock, areas where firewood and other resources could be extracted, and those to be left to regenerate as communal village forest reserves.

Using GIS and historical Landsat imagery, JGI also demonstrated which hillsides have a gradient of more than 45 percent and which were forested in 1972. These insights further help communities draw the line on where it was safe to plant crops and where trees were needed to regenerate and re-stabilize the watershed.

“In the fourteen villages around Gombe National Park, every village set aside land for conservation along the ridge tops and steep slopes,” explained Emmanuel Mtiti, JGI’s program manager for the Greater Gombe Ecosystem Program. “Together, these conservation areas are establishing a forest corridor along the Greater Gombe Ecosystem, protecting the watershed for the benefit of all those who call the region home.”

Recently, Google Earth added more high-resolution satellite imagery focusing on the time period since JGI’s village land use and community forest monitoring efforts began in 2005. “Instead of the forest cover going away, as it had before, the trees are actually coming back!” said Rebecca Moore, engineering manager of Google Earth Engine. “JGI shows us that it doesn’t have to be all doom-and-gloom. By working appropriately in communities and leveraging global assets like NASA’s, JGI shows us the kind of success that organizations can achieve.”

In communities, people are experiencing this success on-the-ground as well. “There is peace of mind that the land beneath the school won’t give way,” Mtiti said. “More peace of mind that someone won’t lose their crop—their livelihood—in a landslide.”

As for the fishers, Mtiti added, “Off Kitwe, where the forest has returned, the fishermen line up every night again. This intricate system of life and resources—it’s all starting to work better now.”

The conservation of Gombe’s chimpanzees goes hand-in-hand with the conservation of the area’s watersheds. As tree cover returns to steep slopes, it not only stabilizes soils, it also creates conservation corridors that allow female chimpanzees from outside Gombe to join chimpanzee communities within the park—a vital DNA lifeline to ensure the long-term survival of the chimpanzees of Gombe National Park.

“When I arrived in Gombe 50-plus years ago, looking up at the stars, it never occurred to me that one day, we’d be relying on remote sensing—satellites circling the globe high above—to help unite communities of people and save Gombe’s chimpanzees,” said Jane Goodall, a UN Messenger of Peace. “NASA—through its resources and data and funding—is helping us to apply the kinds of innovative solutions needed to address the complex problems people and chimpanzees face today.”

Now, when Goodall sits on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, staring out as moonlight mingles with the lights of fishers’ compression lamps, she knows JGI isn’t in this work alone. A small constellation of organizations, including NASA and Google Earth Outreach, are helping the Gombe region become a place where people can be safe from landslides and have the food and water they need. A place where, as fishers return with their catch in the morning, they can still hear the far-off pant-hoots of chimpanzees whose day is just beginning.

About the science: JGI used Landsat MSS and ETM+ satellite images from 1972 and 1999 to calculate the loss of forest and woodland cover during that time.

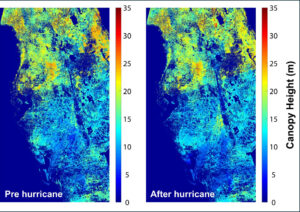

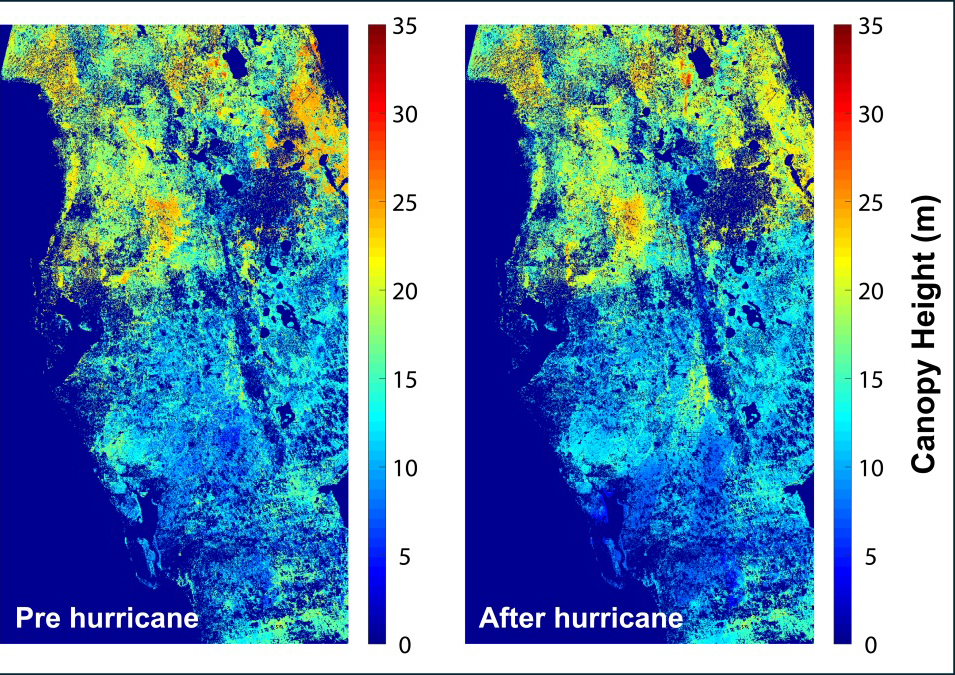

Mapping Forest Damage from Hurricane Milton on Florida’s West Coast

Rising sea levels and increased ocean temperatures are supercharging hurricanes. Using satellite data can help monitor vulnerable ecosystems.