By Laura E.P. Rocchio

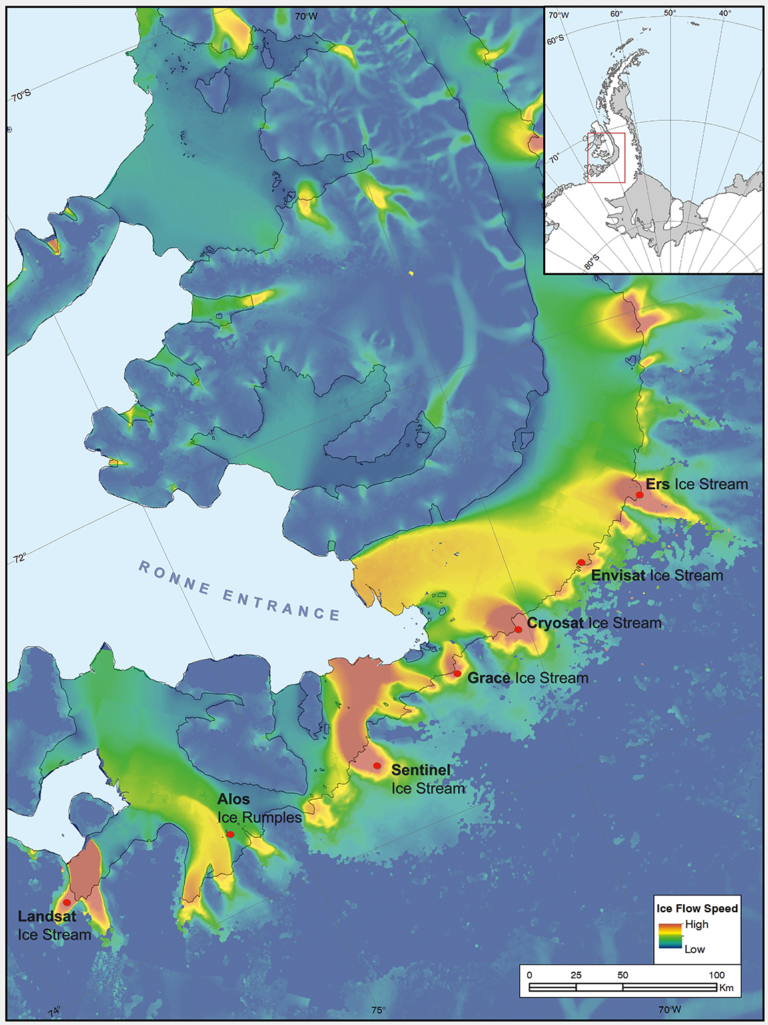

The UK’s Antarctic Place-names Committee has agreed that seven ice features in western Antarctica should be named for Earth-observation satellites. One of them is Landsat Ice Stream.

The new designations were announced on June 7, 2019. The ice features are all located in Western Palmer Land on the southern Antarctic Peninsula.

The seven features ring George VI Sound like pearls on a necklace. The new names, as officially entered into the British Antarctic Territory Gazetteer, are (from west to east): Landsat Ice Steam, ALOS Ice Rumples, Sentinel Ice Stream, GRACE Ice Stream, Envisat Ice Stream, Cryosat Ice Stream, and ERS Ice Stream.

The new names were proposed by Anna Hogg, a glaciologist with the Center for Polar Observation and Modelling at the University of Leeds. In research published in 2017, Hogg found that glaciers draining from the Antarctic Peninsula were accelerating, thinning, and retreating, with implications for global sea level rise.

Satellites had enabled Hogg and her team to clock the speed of these nameless ice features—some with rates faster than 1.5 meters/day.

The fast-moving glaciers that Hogg and colleagues tracked with radar and optical satellite imagery were unnamed. In her paper, the glaciers had to be designated by latitude and longitude.

In tribute to the spaceborne instruments that enabled her research, Hogg came up with a way to describe the fast-moving ice features more succinctly—name them after the satellites she had used to understand their behavior.

Hogg proposed to the U.K.’s Antarctic Place-names Committee that the features should be named for Landsat, Sentinel, ALOS PALSAR, ERS, GRACE, CryoSat, and Envisat. She was notified in early June that the committee had agreed to adopt the names, which provide a way to recognize international collaboration, as fifteen space agencies currently collaborate on Antarctic data collection.

“Satellites are the heroes in my science of glaciology,” Hogg told the BBC. “They’ve totally revolutionized our understanding, and I thought it would be brilliant to commemorate them in this way.”

The UK has submitted the new names for the fast-moving ice features to Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) which maintains a gazetteer, or registry, of names officially adopted by individual nations. Under the Antarctic Treaty, signatory nations confer on geographic feature names, but each nation’s naming authority formally adopts new names.

The U.S. Board on Geographic Names will meet in July and may discuss at that meeting whether the names adopted by the UK also will be adopted by the US. The question of using the term “glacier” for the ice features instead of “ice stream” is also part of each nation’s naming decision.

Update: July 16, 2019 • The Committee on Antarctic Names and the U.S. Board on Geographic Names have now made the satellite ice stream names official.

Naming the glaciers after satellites is also a celebration of data fusion. “Our understanding of ice velocities and ice sheet mass balance has come from putting many different remote sensing data sets together—optical, radar, gravity, and laser altimetry,” said Jeff Masek, the NASA Landsat 9 Project Scientist.

“Landsat has been a key piece in assembling that larger puzzle. Naming an ice stream after Landsat is a fitting way to recognize the value of long-term Earth Observation data for measuring changes in Earth’ polar regions.”

Landsat: An Antarctic Pioneer

Antarctica is one of the world’s most remote locations and the coldest and highest continent. It is also massive: nearly one and half times the size of the United States (including Alaska). It is difficult to study without satellites.

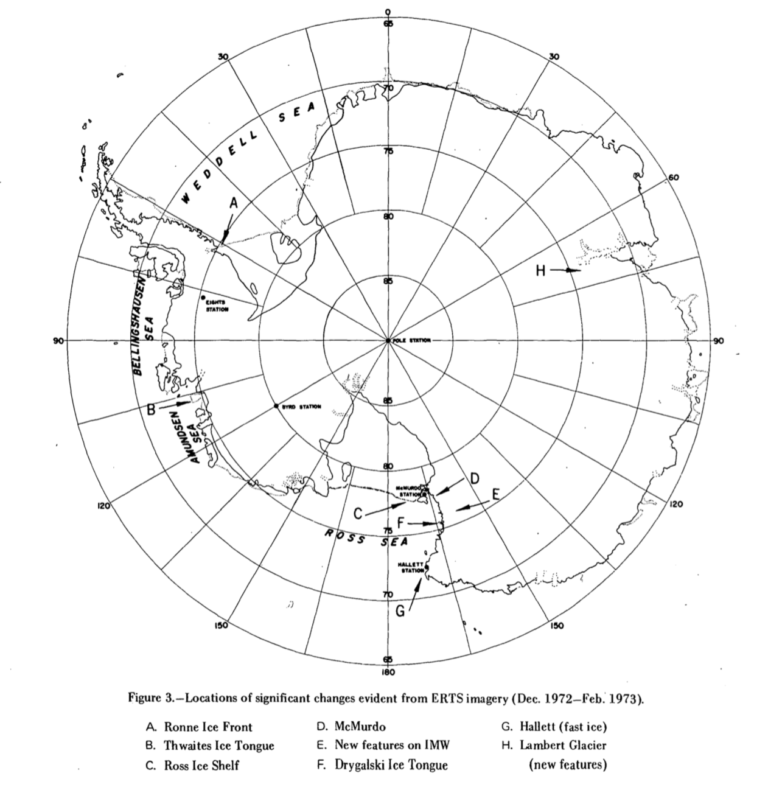

When the first Landsat launched in 1972, the far side of the moon was better mapped than Antarctica . Landsat gave researchers an accurate way to measure the size of its ice sheets and glaciers and estimate average flow rates.

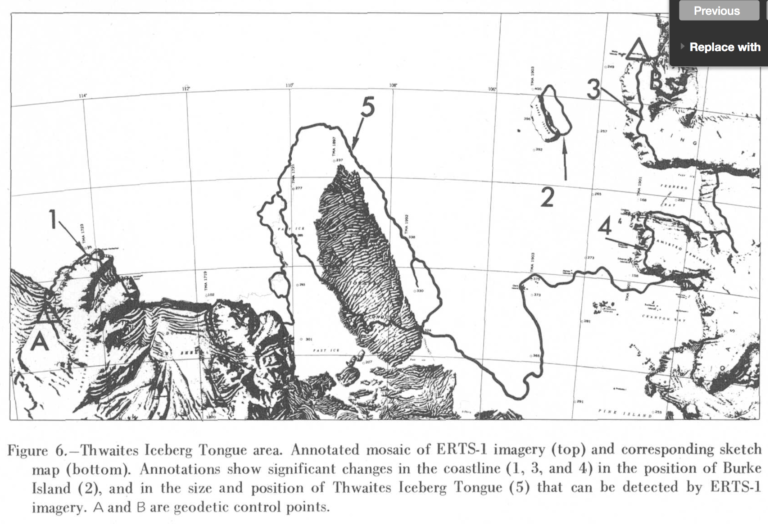

Landsat 1 (then called ERTS-1) helped cartographers establish correct positions for Antarctic shorelines, ice shelfs, and islands. For instance, Landsat showed Franklin Island to be 7.2 km south of its charted location, confirming a problem U.S. ships had reported for years.

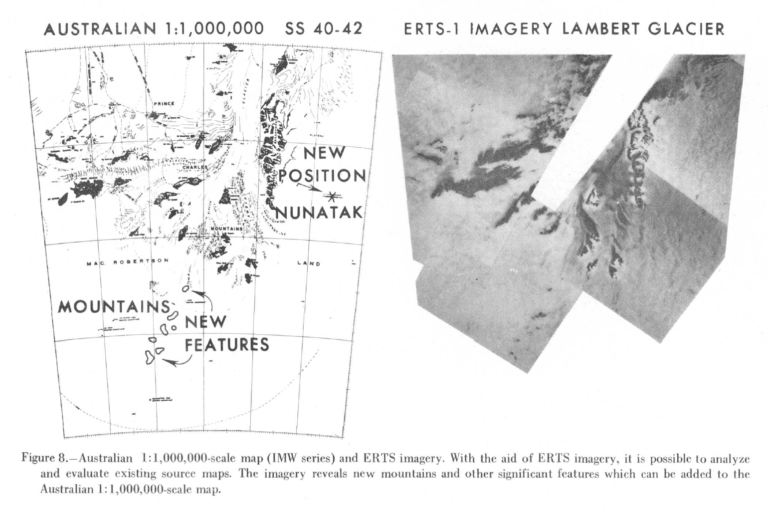

The satellite also showed formerly uncharted mountains at the head of Lambert Glacier and helped identify areas of blue ice in Victoria Land (where meteorites where found during subsequent field seasons).

In 1978, the U.S. Geological Survey published the first chapter of an 11-chapter paper titled, Satellite Image Atlas of Glaciers of the World, based on Landsat 1, 2, and 3 data. The second chapter focused on Antarctica and The work established a baseline of Antarctic glacier extent as observed between 1972 and 1982 (Chapter 2 ).

For the 2007-2008 International Polar Year, more than one thousand Landsat 7 images were mosaicked into the most detailed satellite image of Antarctica.

The Landsat Image Mosaic of Antarctica (LIMA) Project Investigator, Robert Bindschadler, explained at the time: “Researchers have often felt hampered by trying to understand what the ice sheet is doing by working on its surface. It is much like trying to understand the United States when remaining in your own neighborhood. To see the major features important to Antarctic flow dynamics, I needed my eyes placed hundreds of kilometers above the ice sheet. Landsat data gave me that view.”

Most recently, Landsat 8, with its improved signal to noise ratio and increased data collection rate, has helped researchers study the continent.

The GoLIVE project has used Landsat 8 data to provide near-real-time information on every large glacier, and the British Antarctic Survey has used Landsat 8 data to map all Antarctic rock outcrops.

Into the Polar Night

As the height of polar night approaches in Antarctica, the newly named Landsat Ice Stream continues its flow into the Stange Ice Shelf. Landsat 7 and 8, together with an international fleet of satellites, keep collecting data over one of the most hostile and isolated places on the planet.

Landsat is a joint mission of NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey.

Related Reading:

+ Antarctic glaciers to honor ‘satellite heroes’, BBC News

+ Celebrating satellites’ contribution to Polar science, CPOM

+ Antarctic Glaciers Named After Satellites, ESA

+ Antarctic Ice Streams named after Earth Observation Satellites, SCAR Community News

+ Seven Newly Named Glaciers Honor the Satellites That Helped Discover Them, Gizmodo

+ Collected stories about Landsat and Antarctica

Correction, June 27, 2019: SCAR’s role in the Antarctic naming process was incorrectly described in the earlier version of this article. Updates to correctly describe the naming process were provided by Dr. Scott Borg, Deputy Assistant Director of the National Science Foundation’s Directorate for Geosciences, and Peter West, the Outreach Program Manager for NSF’s Office of Polar Programs.

The UK submitted these names to the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) which maintains a gazetteer of names officially adopted by individual nations. Under the Antarctic Treaty, signatory nations confer on geographic feature names, but each nation’s naming authority formally adopts new names. The U.S. Board on Geographic Names will met in July and adopted the name. The question of using the term “glacier” for the ice features instead of “ice stream” is also part of each nation’s naming decision.