By Sarah Johnson, Landsat Science Writing Intern

With its oversized furry ears, dark round eyes, pink button nose, and long fluffy tail, Australia’s greater glider could be mistaken for a beloved toy animal. The cat-sized marsupial can glide as far as 100 meters between treetops, but its forest habitat is shrinking. Over the past two decades, the greater gliders population has dwindled by 80 percent, landing the nocturnal possum on Australia’s endangered species list.

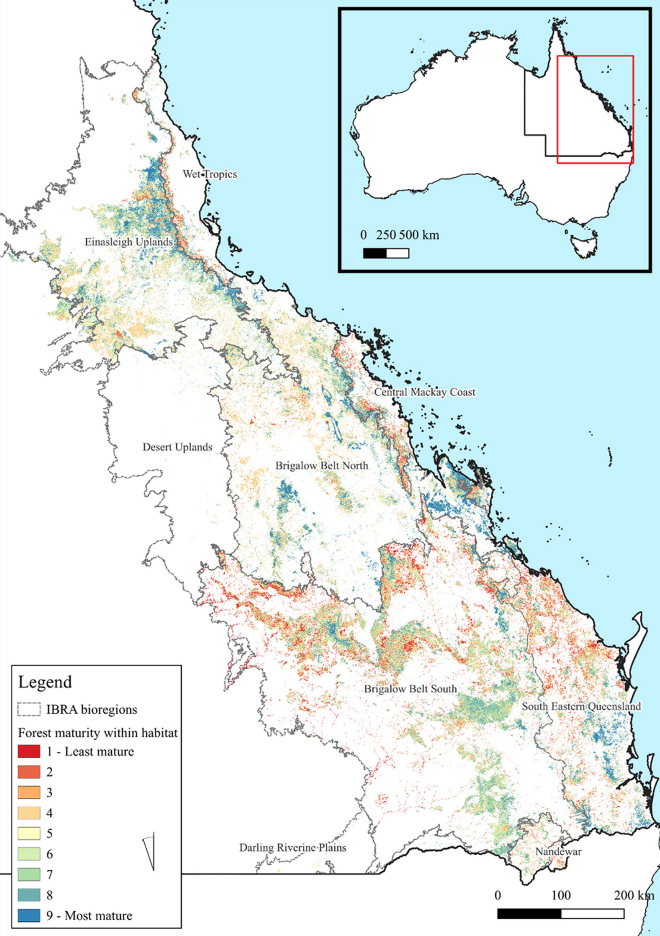

In a paper recently published in Pacific Conservation Biology, Griffith University researchers found that less than 13 percent of the endangered species’ habitat in Queensland is protected. The researchers utilized satellite data, including Landsat, to map forest maturity and identify areas of favorable glider habitat.

Greater gliders rely on hollows in mature eucalyptus trees for shelter. These tree hollows can take a long time to form and are usually found in trees more than 150 years old. In turn, these hollows leave mature trees more susceptible to destruction in forest fires. Australia’s forests are continually threatened by bushfires, timber harvesting, forest clearing for urban development, and climate change. Climate change can be particularly stressful for forest-dependent creatures such as these gliders, inflicting potentially detrimental effects such as excess rainfall and increased temperatures.

Queensland’s forests and woodlands have been afflicted with higher amounts of rainfall and experienced a devastating series of bushfires in the 2019-2020 summer season. These fires wiped out many mature trees, destroying critical glider habitat and killing a profusion of wildlife.

Mapping Maturity

To get a good sense of how mature a forest is, a combination of data is necessary.

For their eastern Queensland study region, researchers used Landsat products to map forest cover, GEDI lidar data to map forest height, and GlobBiomass data to assess forest density and biomass.

Together, these different datasets were used to measure forest aspects crucial for determining maturity. Mature trees are more likely to have hollows—the critical habitat for greater gliders.

Note: Four Landsat-derived datasets were used in this study:

Preserving Australia’s Largest Gliding Possum

Old-growth eucalyptus woodlands, with their shelter-providing hollows and delicious-to-gliders eucalyptus leaves, make up the largest portion of greater glider habitat. Yet, this study revealed that only 12.8 percent of such mature forests are protected. Additionally, intensive logging in state-owned forests has reduced the number of large, old-growth trees through selective harvesting (lumberjacks and greater gliders like the same old trees).

Without mature forest patches and tree-filled corridors for movement, the greater gliders will not be able to survive. The study’s authors say that a conservation intervention and broad collaboration is needed to protect glider habitat across the many regional land ownerships (public, private, and indigenous).

Since the study’s publication in August, there has been a push for the Queensland government to influence the expansion of protected habitat. This research has been sent to the Queensland Department of Environment and Science and has been picked up by smaller government councils. In combination with the Queensland Department of Environment and Science’s own research on glider mapping, this could mean great improvements in the conservation of glider habitat.

The maps generated by this study can inform biodiversity networks and land management. It is not just the gliders that are affected by unprotected habitat; there are around 300 more species that require these same forests to live and thrive. By protecting the mature forests, it is possible to preserve all these species.

Reference

Norman, Patrick, and Brendan Mackey. 2023. “Priority areas for conserving greater gliders in Queensland, Australia.” Pacific Conservation Biology:-. doi: https://doi.org/10.1071/PC23018.Related Reading

The precarious nature of greater glider habitat in Queensland, Cosmos

Guide to greater glider habitat in Queensland, Queensland Department of Environment and Science

Sarah Johnson is a senior at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. She is graduating this month from UMBC’s Environmental Science and Geography program. For this story, Sarah interviewed lead author Dr. Patrick Norman from Griffith University in Australia and collaborated with Laura Rocchio from the Landsat Outreach team on the text.