By Morgan Spehar, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

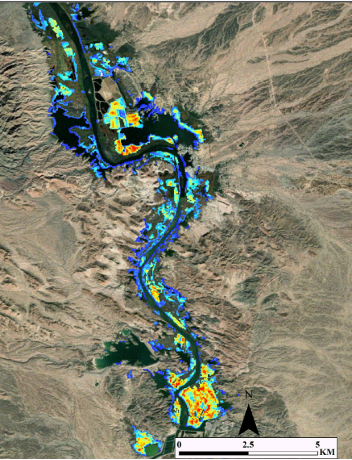

The Yuma Ridgway’s rail, a chicken-sized bird that looks like a cross between a duck and a crane, hides away in the marshes of the Lower Colorado River. But the habitat of this funny-looking marsh bird is in danger. Using Landsat satellite imagery, researchers have mapped the locations of prime rail habitat to help land managers prioritize management actions for this endangered species.

The Yuma Ridgway’s rail is brown and gray, and can be found in California, Arizona, Nevada and northern Mexico. The rail relies on the cattail marshes in the region, which in turn rely on periodic disturbances–like the flooding of the Lower Colorado River–to reset marsh succession and wash away dead marsh vegetation. These disturbance events help distribute nutrients and maintain a mosaic of high-quality habitat for the rails.

Due to the damming of the Colorado River and other water regulations, flooding in the Lower portion of the river is rare. Emergent wetlands can no longer rely on the natural cleansing of the floods, and as a result the Yuma Ridgway’s rail has been left with much less available habitat.

“Rails are marsh birds, and they live in emergent marshes that are often dominated by cattails in the southwestern United States,” explained Eamon Harrity, a researcher at the University of Idaho. “In the absence of disturbance, old, dead vegetation accumulates in the marshes and can eventually reduce the quality of foraging and nesting habitat.”

Using Landsat

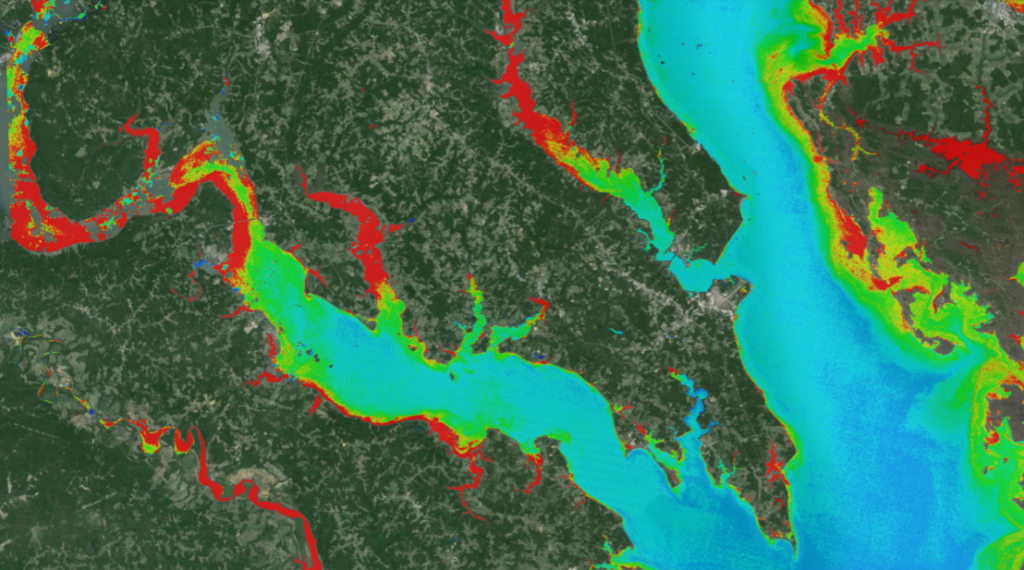

Working with other researchers from the University of Idaho and the U.S. Geological Survey, Harrity used Landsat imagery and the processing power of Google Earth Engine to model the best habitat for rails along the Lower Colorado. Landsat is a joint mission of NASA and the USGS.

The researchers used medium-resolution Landsat imagery from 1999 to 2019, as well as rail count information to look at a broad swath of potential habitat and find where the rails were most likely to thrive. That sheer amount of data, however, can make remote sensing satellite information hard to work with. Software that can process the information can be expensive and difficult to use. Advances in cloud computing have made it easier to overcome these difficulties and made satellite data easier to work with.

This made it easier for the researchers to focus on the benefits of using Landsat images, including its extensive data archive.

“First of all, it’s freely available,” Harrity said. “Second of all, it balances the spatial and temporal resolution that we wanted. Landsat allowed us to get medium-resolution, biweekly imagery dating all the way back to the late 1990s.”

About the Rail Efforts

The Yuma Ridgway’s rail has many of the hallmarks of an endangered species: it has a limited range, a limited amount of habitat available and it competes with humans for one of the most precious resources in the desert Southwest: water.

The good news for the rail is that researchers have effective methods to compensate for the lack of flooding and maintain high-quality rail habitat. Manually burning, flooding or otherwise clearing out dead vegetation in the marshes can reset marsh succession and stimulate new cattail growth. Land managers know how to create prime habitat for rails, they just don’t always know where to direct their efforts.

“We have management tools to help maintain quality habitat for the rails,” Harrity said, “we just didn’t have effective ways to guide the application of those management tools…so that’s the gap or niche that this study is trying to fill.”

Because the rail has many of the characteristics of a typical endangered species, the methods of the study – identifying habitat with Landsat and on-the-ground data – could be applied elsewhere.

The authors created a framework that other researchers can use when looking to map habitat that is suitable for an endangered species. They also created a Google-based app that is available to the public to showcase their habitat models for the rail.

“By taking our modeling effort and putting it into an application, we made it more accessible,” Harrity said. “The intended audience is really the land managers and the biologists who work with this species on a daily basis. We wanted to provide them with a tool that they can use to see annual maps of habitat suitability and how it changes over time.”

The Future

The study authors hope to expand their models using rail count data that goes all the way back to the 1970s, to further improve the accuracy and expand the temporal scope of the habitat suitability predictions.

Harrity ‘s research has shown that while there is marsh habitat available, not all of it is optimal for the rails. But he remains optimistic and hopes the range-wide map that they created can help managers prioritize their management and improve habitat for the rails at a broader scale.

“High-quality rail habitat is very limited,” he said. “But at the same time, we saw that most of the high-quality rail habitat that does exist is currently protected or on federally managed land, which suggests that the management actions are working.”

Reference:

Harrity, Eamon J., Bryan S. Stevens, and Courtney J. Conway. 2020. “Keeping up with the times: Mapping range-wide habitat suitability for endangered species in a changing environment.” Biological Conservation 250:108734. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108734.