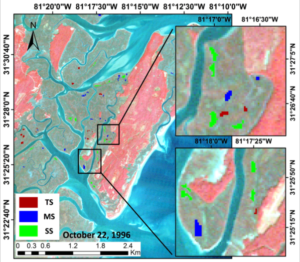

Using data collected by NASA’s Landsat TM 5 satellite, which provided 28 years of nearly continuous images of the Earth’s surface between 1984 and 2011, the researchers found that the amount of marsh plant biomass had dropped 35 percent. They published their findings recently in the journal Remote Sensing.

This sharp decline is largely due to changes in climate, the researchers report, with prolonged periods of drought and increased temperatures playing a major role. And scientists worry that this loss of vegetation will have a ripple effect throughout the complex marsh-based ecosystems.

“A decrease in the growth of marsh plants likely affects all of the animals that depend on the marsh, such as juvenile shrimp and crabs, which use the marsh as a nursery,” said Merryl Alber, director of the Marine Institute and UGA professor of marine sciences. “These decreases in vegetation may also affect other marsh services, such as stabilizing the shoreline, filtering pollutants and protecting against storm damage.”

The research was conducted by John Schalles, professor of biology at Creighton University in Nebraska and adjunct professor of marine science at UGA, and John O’Donnell, a graduate student in Creighton’s department of atmospheric sciences.

The use of satellites allowed Schalles and O’Donnell to observe large swaths of cordgrass marshland without enduring the hardships and expense of extensive field work.

“Salt marshes are muddy environments that are difficult to navigate, and you have to carefully plan your expeditions for low tide,” said O’Donnell, who spent a year in residence at the UGA Marine Institute while conducting his research. “The use of the satellite allowed us to get data from a much larger area than what could be collected in the field. It also allowed us to go back in time.”

Ultimately, both Schalles and O’Donnell hope that their satellite-based study of marshland will continue on Sapelo Island, as well as in other coastal regions throughout the world.

“We plan to extend this work over the coming years and use it to help predict how marshes will respond to sea level rise and other long-term change,” Schalles said.

The project was supported by the Georgia Coastal Ecosystems Long Term Ecological Research Project, an ongoing study of the salt marsh ecosystem of the Georgia coast based at the Marine Institute and funded by the National Science Foundation. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration also provided funding for the study.

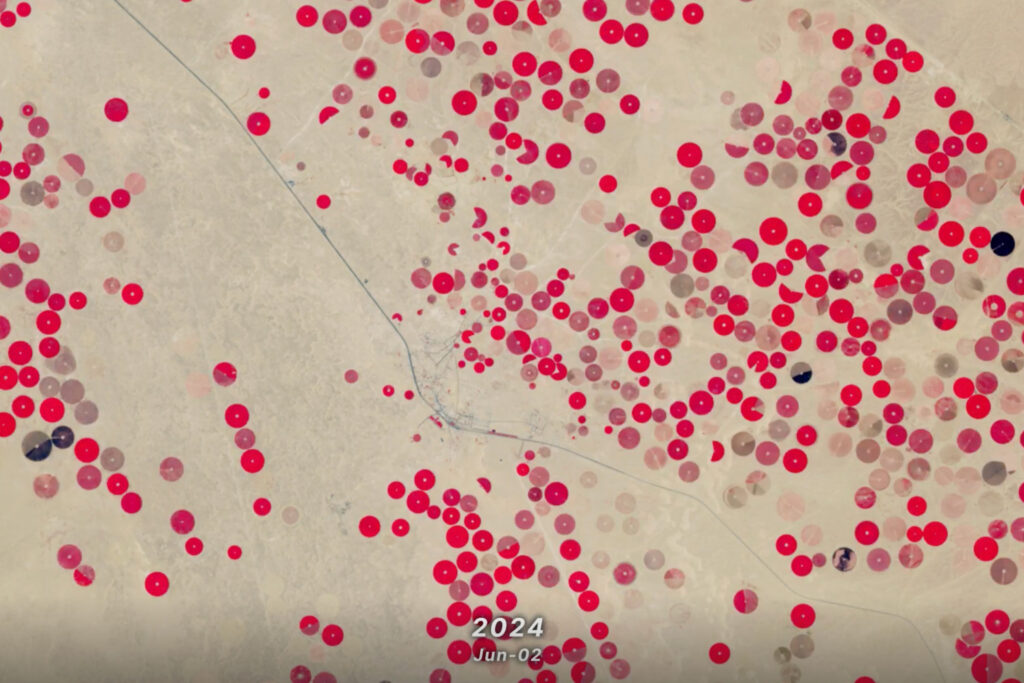

Saudi Arabia’s Desert Agriculture

In this animation of 2024 and January 2025, crop fields in Saudi Arabia cycle through their growing seasons.