Mangrove forests are an iconic feature of the Florida Everglades, their half-submerged roots forming tunnels for kayaking tourists. Beyond their beauty, these trees are important for humans and sea life alike. They stabilize coastlines, slow the movement of tides, store carbon, and help protect against erosion from storm surges. Their tangled root system provides shelter for fish and other organisms.

Mangroves are known to be able to withstand intense flooding, but a new study published in Remote Sensing of Environment found that the increasing frequency and intensity of storms are threatening their resilience. The researchers used data from Landsat satellites to analyze mangrove conditions in Florida from January 1999 through April 2023. They found that as stronger hurricanes hit more often, some mangrove forests are losing their natural capacity to recover.

“Our monitoring has shown a significant increase in the area of mangroves that have lost their natural recovery capacity following recent hurricanes, such as Irma in 2017 and Ian in 2022,” said Zhe Zhu, a co-author of the study and a former member of the USGS-NASA Landsat science team.

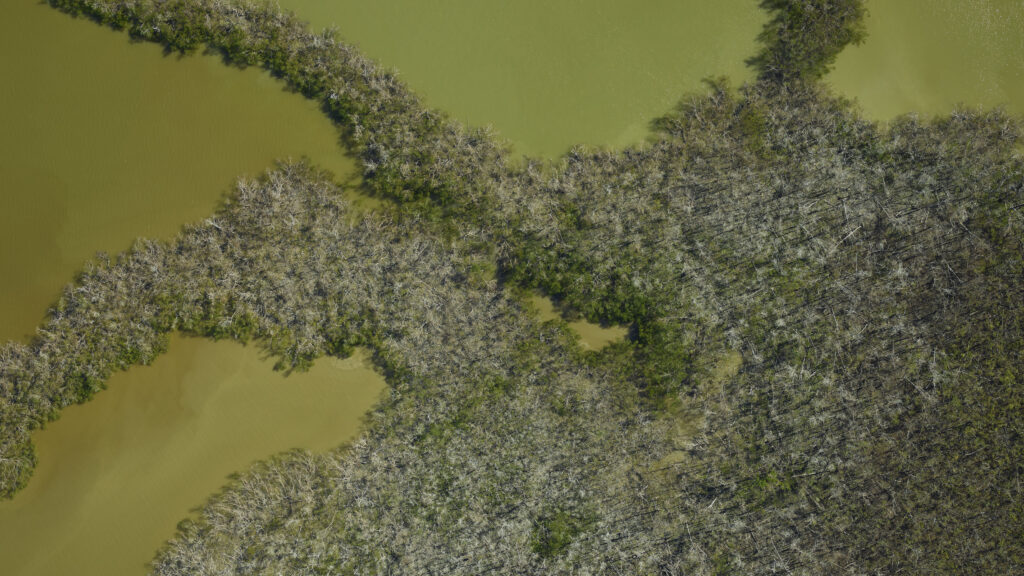

Previous studies have often analyzed a particular disturbance, such as a hurricane, and tracked any losses of mangrove forests after the storm hit. For example, the photo below, acquired by the G-LiHT (Goddard Lidar, Hyperspectral and Thermal Imager), shows mangroves in southern Florida damaged by Hurricane Irma. In the new study, the researchers sought a more complete picture of how mangrove conditions have changed over time, hoping for insight into how these trees recover.

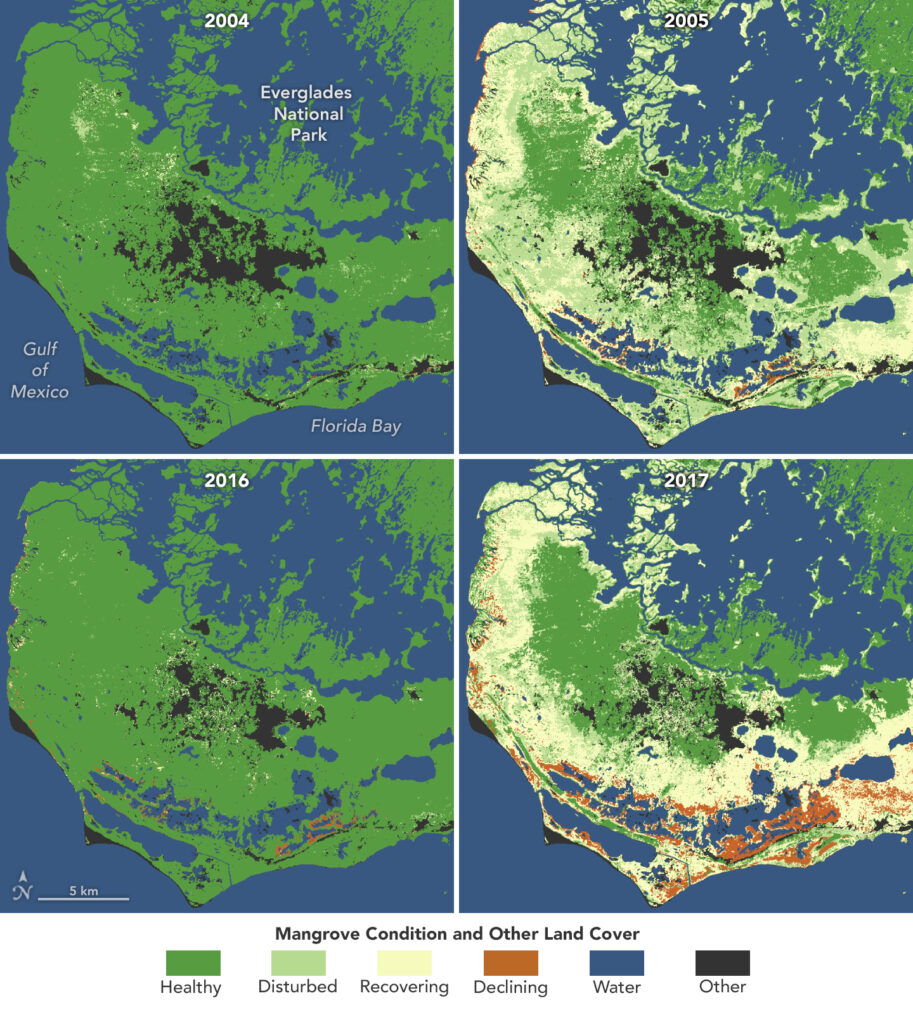

The researchers created four categories of mangrove conditions: healthy, disturbed, recovering, and declining. A healthy mangrove forest shows no change when hit by a storm. A disturbed mangrove is affected by a storm, but it rebounds to a healthy state within the same growing season. A recovering mangrove takes longer than one growing season to rebound. A declining mangrove is one that does not recover naturally after a disturbance but instead faces long-term decline.

The benefit of this satellite-based approach is that it allows for continuous monitoring of mangrove conditions. Researchers can capture disturbances as they happen. They used a machine learning algorithm to classify mangrove conditions, which can be continually updated as new Landsat data becomes available. It can also provide early identification of the signs of a declining mangrove, alerting land managers as to where they should focus their efforts.

“Our research aims to provide an early warning system for mangrove decline, helping to identify areas at risk before irreversible loss occurs,” Zhu said.

One of the clearest ways to visualize the changing resilience of mangrove forests is to compare the recovery from different disturbances. The maps at the top of this page, composed using the Landsat-based algorithm, indicate the condition of mangroves in the southern Everglades National Park bordering the Gulf of Mexico.

The maps show mangrove status before and after Hurricane Wilma in 2005 and Hurricane Irma in 2017, both of which were Category 5 storms. While most damaged mangroves experienced natural recovery after Hurricane Wilma, mangroves in the aftermath of Irma saw a large area of decline (indicated in orange on the map), including some that ultimately became “ghost forests”—a forest of dead trees.

In future work, the researchers hope to expand the study area and work toward a system to monitor mangrove conditions worldwide. Meanwhile, they plan to fine-tune the current algorithm to better understand the different drivers of mangrove change.

“By identifying whether changes are driven by extreme weather events, rising sea levels, or human activities, we can provide more targeted insights for conservation and management strategies in a rapidly changing environment,” Zhu said.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, using data from Yang, Xiucheng, et al. (2024). Gif by Xiucheng Yang.