Fieldwork is an essential part of this work—Pelto is just back from his 30th field season in the North Cascades where he took snow depth and snowmelt measurements while mapping terminus positions for a dozen glaciers. Such fieldwork provides ground truth information for specific points, which helps scientists understand how conditions on the ground are changing from year to year. But satellite imagery from Landsat provides the big picture perspective that enables the point data to be understood in a regional and global context.

“Without the images, we would just have the isolated point measurements of ground truth at specific times” Pelto explains. “Such limited measurements are hard to extrapolate to the larger glacier without the satellite truth.” Together, the field and satellite data can provide an accurate picture of how the cryosphere is being altered.

The bulk of Pelto’s published research focuses on the glaciers of Alaska, Washington, and British Columbia where he does regular fieldwork. However, on his blog, From A Glacier’s Perspective, Pelto provides detailed assessment of 300 glaciers around the world using freely available satellite data—mostly Landsat. Because many of the world’s glaciers are remote and difficult to access, local maps are often out-of-date in this period of rapid glacier change.

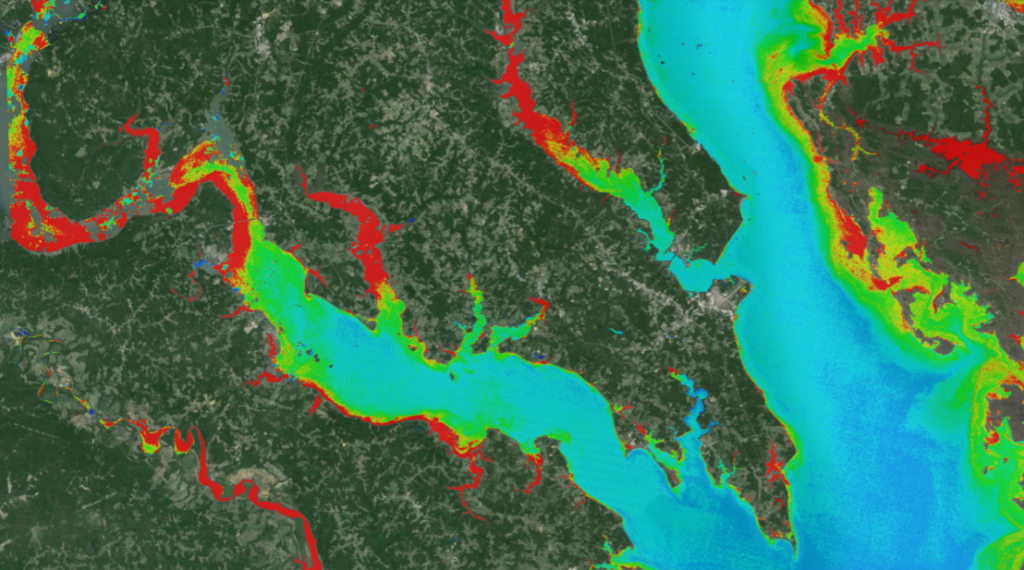

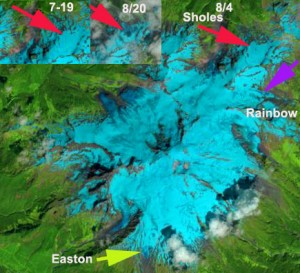

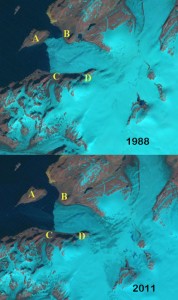

By tracking prominent visual features on satellite images, Pelto can better map “changing glacier outlines, snow lines, glacial lakes and glacier velocity.” Given the long record of Landsat data, historic glacier imagery can be compared to recent imagery to better understand changes happening around the planet.

One of the most interesting changes Pelto has noticed over the last three decades is the large number of new alpine lakes formed (and dramatically expanded) as glaciers have retreated in the Alps, Himalayas, Andes, North America, New Zealand, and Norway. He has also witnessed the exposure of islands off the coast of Greenland and Novaya Zemlya that had been veiled in ice for millennia.

A geologist by training and avid skier by avocation, Pelto found that the field of glaciology married his two passions. Since first seeing Landsat used at an International Glaciology conference in 1983, satellite imagery has been a part of his research repertoire, especially for the Juneau Icefield.

“Landsat imagery has played a critical role providing information on glaciers that I otherwise simply would not have had access to,” Pelto says.

“Studying the changing glaciers using Landsat is something that I do almost everyday, and continues to bring joy and discovery.”

Pelto’s daughter Jill (University of Maine) and son Ben (University of Mass., Amherst) are regularly involved in his North Cascade field expeditions now, helping him track summertime snow depth and snowline migration in the field. A technique he has extrapolated more broadly using multi-date satellite imagery. The decision to make the entire Landsat archive free has made this research possible.

“Much of the research I now focus on requires so many images that I could not have afforded to acquire them in the past,” Pelto explains.

“It is great to have Landsat so readily available, it is a game changer for many of us researchers that are not at large research institutions and do not have deep pockets.”

Contributor: Laura E.P. Rocchio

Be Part of What’s Next: Emerging Applications of Landsat at AGU24

Anyone making innovative use of Landsat data to meet societal needs today and during coming decades is encouraged to submit and abstract for the upcoming “Emerging Science Applications of Landsat” session at AGU24.