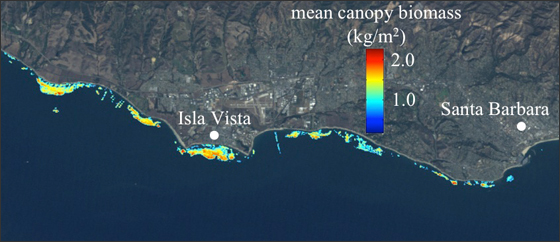

In this marriage of marine ecology and satellite mapping, the team of UCSB scientists tracked the dynamics of giant kelp––the world’s largest alga––throughout the entire Santa Barbara Channel at approximately six-week intervals over a period of 25 years, from 1984 through 2009.

David Siegel, coauthor, professor of geography and codirector of UCSB’s Earth Research Institute, noted that having 25 years of imagery from the same satellite is unprecedented. “I’ve been heavily involved in the satellite game, and a satellite mission that goes on for more than 10 years is rare. One that continues for more than 25 years is a miracle,” said Siegel. Landsat 5 was originally planned to be in use for only three years.

Forests of giant kelp are located in temperate coastal regions throughout the world. They are among the most productive ecosystems on Earth, and giant kelp itself provides food and habitat for numerous ecologically and economically important near-shore marine species. Giant kelp also provides an important source of food for many terrestrial and deep-sea species, as kelp that is ripped from the seafloor commonly washes up on beaches or is transported offshore into deeper water.

Giant kelp is particularly sensitive to changes in climate that alter wave and nutrient conditions. The scientists found that the dynamics of giant kelp growing in exposed areas of the Santa Barbara Channel were largely controlled by the occurrence of large wave events. Meanwhile, kelp growing in protected areas was most limited by periods of low nutrient levels.

Images from the Landsat 5 satellite provided the research team with a new “window” into how giant kelp changes through time. The satellite was built in Santa Barbara County at what was then called the Santa Barbara Research Center and launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base. It was designed to cover the globe every 16 days and has collected millions of images. Until recently these images were relatively expensive and their high cost limited their use in scientific research.

However, in 2009, the entire Landsat imagery library was made available to the public for the first time at no charge. “In the past, it was not feasible to make these longtime series, because each scene cost over $500,” said Kyle C. Cavanaugh, first author and UCSB graduate student in marine science. “In the past, you were lucky to get a handful of images. Once these data were released for free, all of a sudden we could get hundreds and hundreds of pictures through time.”

Giant kelp grows to lengths of over 100 feet and can grow up to 18 inches per day. Plants consist of bundles of ropelike fronds that extend from the bottom to the sea surface. Fronds live for four to six months, while individual plants live on average for two to three years. According to the article, “Giant kelp forms a dense floating canopy at the sea surface that is distinctive when viewed from above. …Water absorbs almost all incoming near-infrared energy, so kelp canopy is easily differentiated using its near-infrared reflectance signal.”

Cavanaugh explained that, thanks to the satellite images, his team was able to see how the biomass of giant kelp fluctuates within and among years at a regional level for the first time. “It varies an enormous amount,” said Cavanaugh. “We know from scuba diver observations that individual kelp plants are fast-growing and short-lived, but these new data show the patterns of variability that are also present within and among years at much larger spatial scales. Entire forests can be wiped out in days, but then recover in a matter of months.”

Satellite data were augmented by information collected by the Santa Barbara Coastal Long Term Ecological Research Project (SBC LTER), which is based at UCSB and is part of the National Science Foundation’s Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) Network. In 1980, the NSF established the LTER Program to support research on long-term ecological phenomena. SBC LTER became the 24th site in the LTER network in April of 2000. The SBC LTER contributed 10 years of data from giant kelp research dives to the current study.

The scientists said that interdisciplinary collaboration between geographers and marine scientists is common at UCSB and is a strength of its marine science program.

Daniel C. Reed, coauthor and research biologist with UCSB’s Marine Science Institute, is the principal investigator of SBC LTER. Reed has spent many hours as a research diver. He explained: “Kelp occurs in discrete patches. The patches are connected genetically and ecologically. Species that live in them can move from one patch to another. Having the satellite capability allows us to look at the dynamics of how these different patches are growing and expanding, and to get a better sense as to how they are connected. We can’t get at that through diver plots alone. The diver plots, however, help us calibrate the satellite data, so it’s really important to have both sources of information.”

Source: Gail Gallessich & George Foulsham, UC Santa Barbara [external link]

Further Information:

+ UCSB Press Release

Undamming the Klamath

Between October 2023 and October 2024, the four dams of the Klamath Hydroelectric Project were taken down, opening more than 400 miles of salmon habitat.