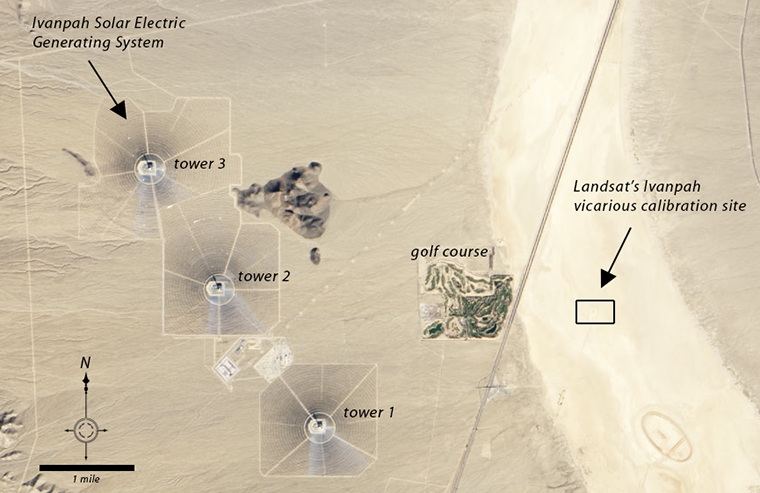

The thermal solar plant uses more than 170,000 moveable mirrors, or heliostats, to follow the sun and focus the sun’s light on central towers filled with water. The water heats up to ~1000ºF creating steam that drives turbines, thereby creating electricity.

Landsat is known for its rigorously calibrated data—i.e., information that accurately reflects physical conditions of the ground. As Belward and Skøien wrote in an April journal article: “Landsat is currently the only satellite program to provide a consistent, cross-calibrated set of records stretching back over more than four decades, which in turn means the program occupies a key position in the provision of terrestrial essential climate variables.”

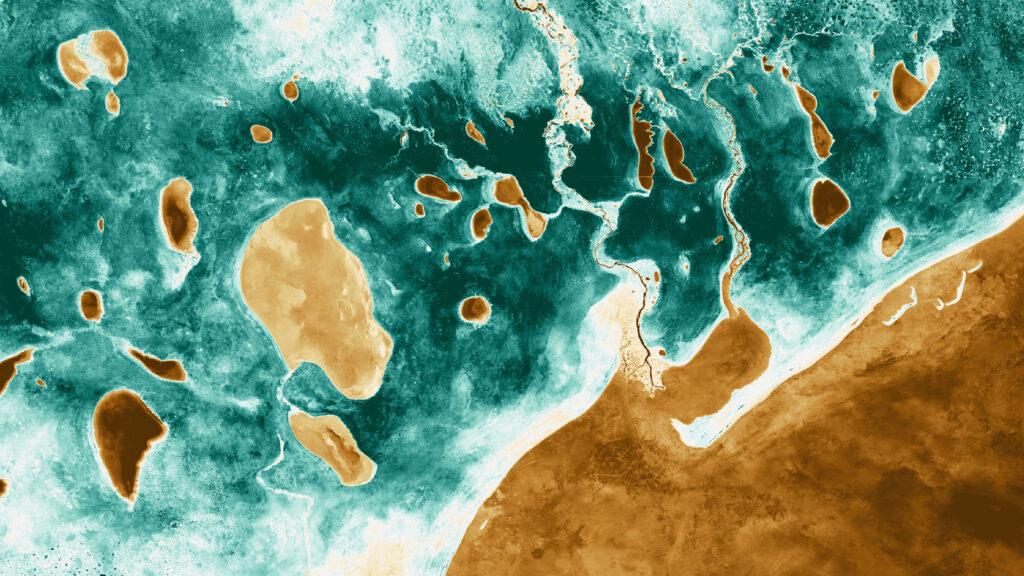

While the Ivanpah solar power plant is generally darker than the playa in the visible Landsat channels, occasionally a Landsat 8 OLI detector or two saturates (i.e. the mirrors reflect more sunlight than the detector was made to measure) when it is acquiring data over this area. So calibration scientists may be able to use the solar plant as a special new calibration target.

Further Reading:

+ Harvesting Sunlight in California, NASA’s Earth Observatory

+ Under Construction: The World’s Largest Thermal Solar Plant, an NPR photo collection

+ Landsat’s Ivanpah Playa Radiometric Calibration Site, USGS