by Pat Brennan, Jet Propulsion Laboratory

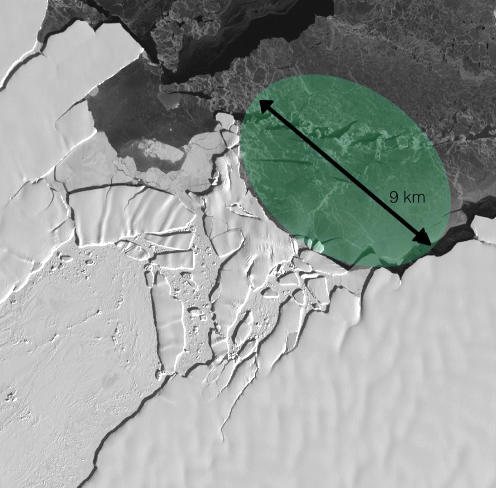

Through satellite images, the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory ice researcher watched the progress of the crash for years. Then she did some quick math, and found the answer. The massive berg, four times the size of Los Angeles, had broken from an East Antarctic ice shelf in 1992, fetching up against an “underwater island” (more formally, a seamount) in 2013.

Over the next five years, a crack zipped down the middle of the iceberg at a rapid clip – more than 270 feet (83 meters) per day – eventually tearing it completely in two.

“The island is uncharted,” Walker wrote in an email. “There is not very much data over the sea floor there, so no one knew that there was an island lurking under the water until this iceberg impacted it.”

As a warming world melts parts of Earth’s polar regions, they draw the focus of scientists, whose instruments reveal previously unknown geography. Seamounts, fjords, trenches and canyons, hidden under ice or covered by water, become increasingly visible.

[This is just an expert. For the full article, please visit the NASA Sea Level Change website.]

Walker, the JPL researcher in Pasadena, California, remains a pioneer in tracking ice changes using traditional satellite photography.

She’s shown that multi-year comparison of these images also can unmask previously unknown geography. A number of researchers are working on automated systems to track such changes using machine learning, but so far, there’s still no substitute for human eyes.

Her image tracking, using a NASA-U.S. Geological Survey satellite called Landsat, is now focused on understanding the velocity of ice movement around rifts – large cracks in the ice.

Walker jokes about her increasingly uncommon – though successful – approach.

“I’m still that sad person who sits there and plots it out,” she said.

How Early Astronaut Photographs Inspired the Landsat Program

In the 1960s, NASA was pioneering a new era of human spaceflight—and astronaut photography—that would change Earth observation forever.