By Laura E.P. Rocchio

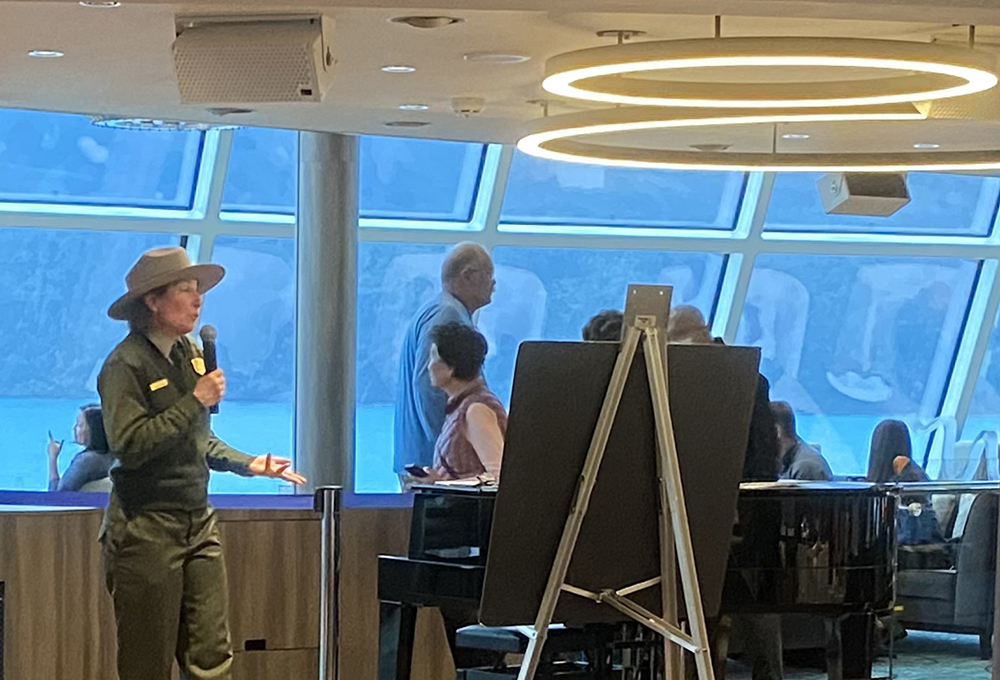

Clambering up the side of a moving ship over chilly waters is just part of the job for National Park Service Ranger Laura Buchheit. Cruise ships are the perch from which 90 percent of visitors to Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve—half-a-million people annually—see the remote park in Southeast Alaska.

As cruise ships make their way from the mouth of Glacier Bay near Bartlett Cove through Sitakaday Narrows (where school bus-sized humpback whales are sometimes spotted), Buchheit and her team of park rangers haul a traveling visitor center aboard, secured by rope.

Once safely aboard, Buchheit and her team share the history of Glacier Bay with the thousands of passengers journeying northward to see the park’s tidewater glaciers.

Nestled in the science-based information that park rangers bring aboard with them are insights from Landsat satellites and NASA climate scientists.

Climate Connections

Climate change is the story of Glacier Bay—both historic natural cycles and modern, human-caused shifts. Three-hundred and fifty years ago, what today is Glacier Bay was a glacial river valley, home to a thriving Tlingit indigenous community. In the 1700s during the Little Ice Age, the Huna Tlingit were forced to abandon their villages and seek shelter on nearby lands as the valley’s massive glacier expanded, reaching its tongue into the waters of Icy Strait, where present-day Glacier Bay empties. That maritime protrusion lasted only a geologic instant before rapidly retreating, leaving Glacier Bay’s open waters in its wake.

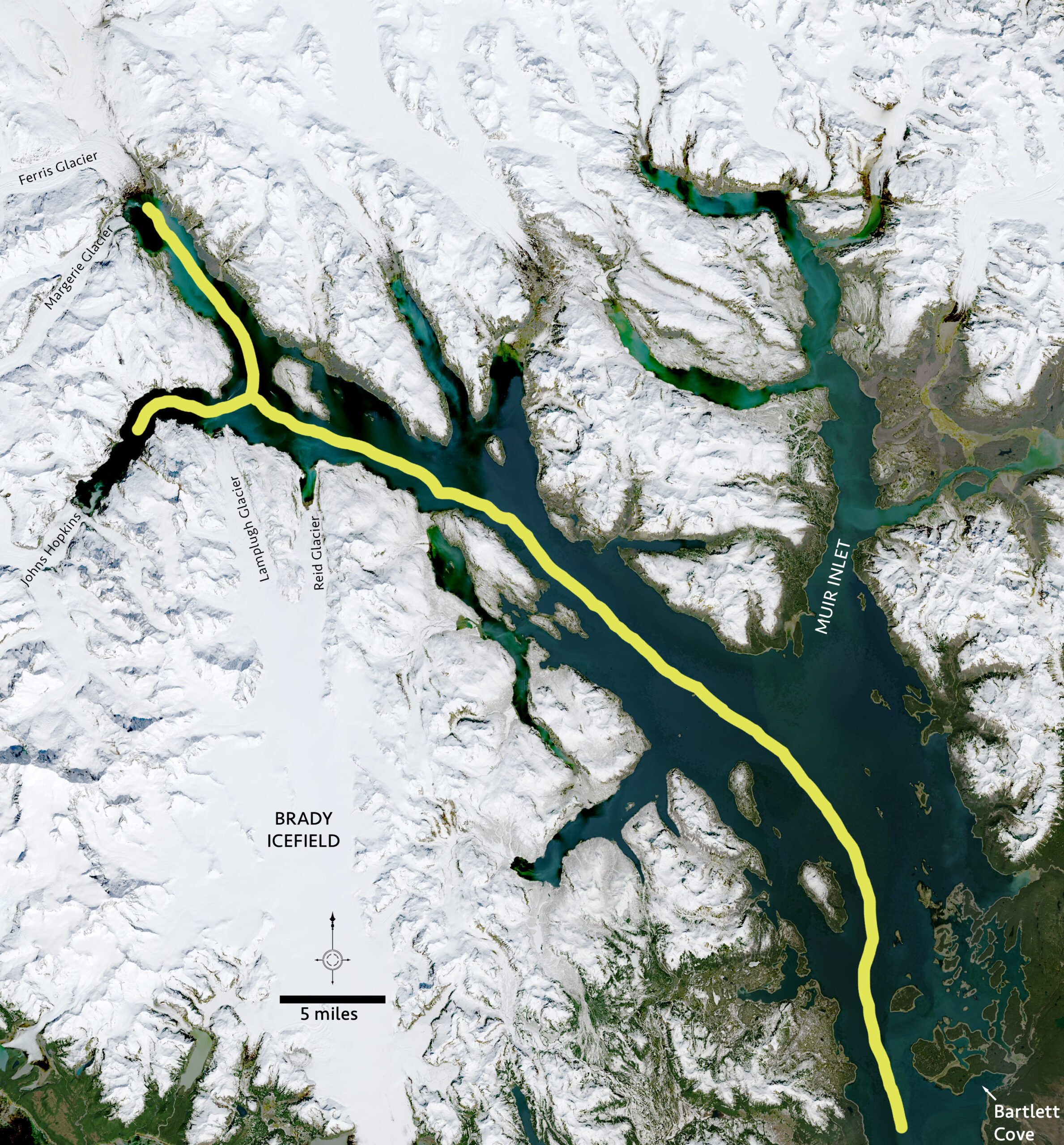

The cruise ship with Buchheit aboard, now five miles into the bay, sails past the point where Captain George Vancouver encountered the active glacier front in 1794; 15 miles on, they pass the mouth of Muir Inlet, where, in 1879, naturalist John Muir first saw the terminus of a glacier that came to bear his name.

Sixty-five miles into the Glacier Bay, in its upper inlets, the cruise ship makes its closest approach to a tidewater glacier.

Standing by the ships’ rails, passengers first see where the rugged Margerie Glacier meets Tarr Inlet. Then they sail on to see the park’s other tidewater glaciers and sometimes witness large blocks of ice fall into the inlet, dramatically calving icebergs. Visitors often describe the glacier viewing experience as spectacular and awe-inspiring.

“Beauty, of and for itself, needs no interpretation,” wrote Freeman Tilden in a foundational 1957 guidebook on park visitor experience, “Later, questions will come.”

This is where park rangers come in.

Rangers create interactive programs to help visitors connect to parks in personally meaningful ways. By sharing what is special about a given place, its historic, cultural, and scientific significance, rangers can awaken visitors’ curiosity and inspire land stewardship.

Park rangers interpret and synthesize research about their parks into digestible stories that give visitors context. When visitors have questions sparked by the surrounding natural beauty, rangers can answer in relatable ways.

Standing on the deck of a ship at sea-level, beholding a massive glacier, the impact of modern, human-caused climate change on Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve can be imperceptible at first, but with a park ranger like Buchheit as a guide, subtle signs can be seen everywhere: the mountain goats grazing in their shrinking alpine habitat; humpback whale populations reduced by half after a marine heat wave, the tremendous marine mammals malnourished and much thinner than before; salmon declines; changing precipitation patterns; smoky conditions from distant burning tundra fires; diminishing glaciers, like Grand Pacific, that no longer reach the bay.

Earth to Sky to Ship

Glacier Bay is a living laboratory for the study of climate change and related ecosystem shifts. A cadre of specialists—biologists, geologists, cultural historians—conduct research at Glacier Bay that informs the programming created by park rangers like Buchheit.

Buchheit has served as the lead for a team of interpretive park rangers at Glacier for the last decade, living year-round in the tiny town of Gustavus that is accessible only by plane or boat. She and her team design and implement Glacier Bay’s in-person programs, outreach materials, and content for web and social media; she knows that good public programming relies on good research.

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve is a massive and mostly roadless place encompassing 3.3 million acres (and it’s part of an even larger World Heritage site). More than a thousand glaciers are found in the park, but only a tiny fraction end in the bay. Most are inland, high in the mountains of Alaska’s wilderness where it takes a birds-eye perspective to witness the changes taking place there: the retreating glaciers, exposed mountainsides, and resulting landslides.

Could tapping into NASA’s satellite-based research provide big-picture insights not easily perceptible from the ground?

Through a colleague, Buchheit was first made aware of an effort called the Earth to Sky Partnership. Earth to Sky provides opportunities for NASA scientists and public land interpreters to collaborate on outreach materials.

Earth to Sky connected Glacier Bay rangers with glaciologist Dr. Christopher Shuman. Using data from NASA/U.S. Geological Survey Landsat satellites, Shuman constructed a nearly 50-year time series of imagery that started in 1972 and showed glacial melt, retreat, increased debris cover, glacier flow changes, and some previously unrecorded landslides.

“The ability to see what was happening through time through Landsat imagery helped us tremendously… from sea-level, we hadn’t seen the signs of retreat that the Landsat imagery showed us—the diminishing of the glaciers, of the size and mass of the glaciers,” Buchheit explains.

“It rocked our world. It truly changed the narrative of interpretation in Glacier Bay. The story that we shared with visitors about glaciers in Glacier Bay was transformed by that information.”

Getting the Earth to Sky Partnership Off the Ground

Glacier Bay provides a vivid example of how Earth to Sky connects science and the power of place by fostering collaborations between scientists, researchers, and interpreters, and enhances the opportunity to share science.

How did Earth to Sky come to be? In 1996, the Public Affairs Office at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center came up with the concept of a “Space Ranger”—a National Park Service Ranger stationed for a year on Goddard’s campus in Greenbelt, Maryland to learn about the types of research done by NASA.

The Park Service accepted, and NASA funded three one-year “Space Ranger” details. The second park ranger detailed to Goddard was Anita Davis, a ranger who had worked at Grand Canyon National Park and at Sunset Crater National Monument (one of the three Flagstaff, Arizona-area National Monuments). Davis was captivated by the cutting edge Earth Science research happening at NASA and intrigued by the possibilities she saw for getting that information into the hands of park interpreters.

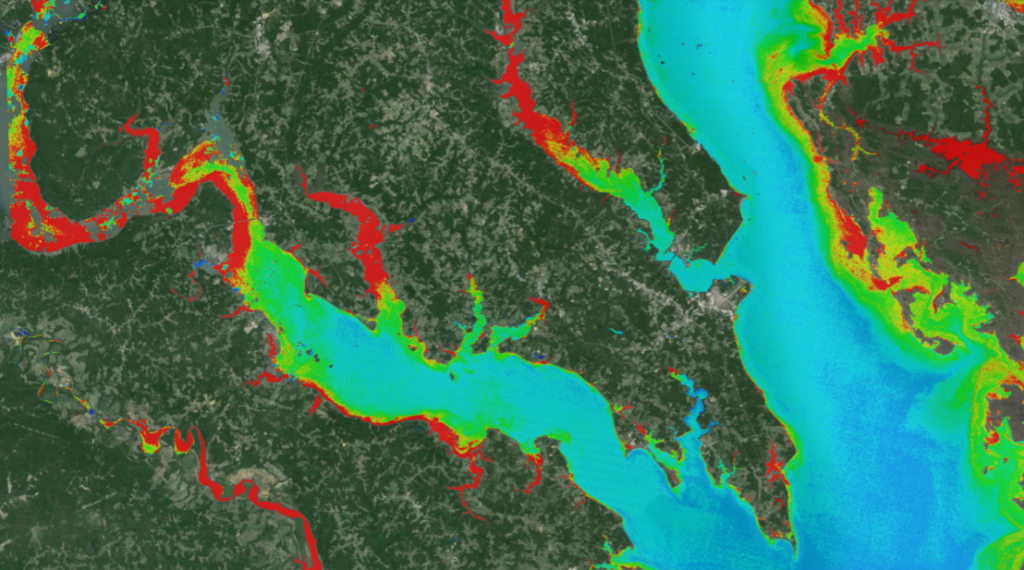

Much of NASA’s Earth Science research was (and is) focused on the human dimensions of global change. Studies were being conducted on deforestation, wildfires, urban growth, glacier retreat, coral reef decline, phytoplankton patterns, severe storm impacts, air quality, and volcanism—all issues relevant to the National Park Service. NASA’s research relied mostly on data from Earth-observing satellites, including Landsat.

Hooked on the exciting research connections she saw, Davis accepted a job at NASA in 2000, and in 2004 became the lead of the Landsat Education and Public Outreach team. That same year, she and the Coordinator of Public Programs at UC Berkeley’s Space Science Laboratory, Ruth Paglierani, worked with the National Park Service to create the first Earth to Sky course. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service joined Earth to Sky in 2008, and by 2012 Earth to Sky was Davis’ full-time job.

Earth to Sky initially crafted courses for National Park Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service participants featuring the breadth of NASA Earth science. In response to interpreters’ requests, Earth to Sky’s major focus shifted to climate change science and communication. As the need for interpreting climate change grew, it became clear that bringing together participants from a common locale and providing them with more targeted climate research would be the most useful approach. Earth to Sky responded by developing regionally-focused courses. With demand for these courses high, the Earth to Sky Academy concept was born—a regionally-distributed, nationally united model to provide more courses and develop additional regional leadership.

The first week-long Earth to Sky Academy took place in October 2019 at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Participants from four regions took part—including Buchheit and her colleagues from southeast coastal Alaska—they now run their own Earth to Sky-style courses, nurturing regional communities of practice.

The second Academy is taking place in mid-October 2022, with five new regions adding to the first four. Buchheit is in attendance again, this time to mentor a new team from Hawaiʻi. Additional Academies are on the horizon.

Earth To Sky’s national leadership team also continues to run individual courses, continuing support of interpreters across the nation and spurring interest in the regional model. Most recently, 25 interpreters from across the Colorado Plateau joined with tribal experts and NASA and local scientists in September 2022 to explore how science and culture inform our understanding and response to climate change.

Course participants become part of the Earth to Sky community, and enjoy a variety of continuing education opportunities, in addition to guidance, support and mentoring.

“For me personally,” Davis shares, “the most gratifying aspect of Earth to Sky is the long term and deep relationships we’ve developed on the team, with scientists, with our participants, and with those who’ve acted as mentors and coaches within our courses.”

Since its 2004 inception, the Earth to Sky community has grown to include over 1500 informal educators from parks, museums, nature centers, and other public lands, all working to improve climate science literacy and environmental stewardship. Landsat, meanwhile, continues to provide the Earth to Sky community with salient information about their local land cover changes, serving as a satellite steward of public lands.