We live amongst an intricate tapestry of ecosystems – ecosystems that, for the last 50 years, Landsat has kept close watch on from orbit. Landsat’s vast decades-long archive provides researchers a unique opportunity to study the surface of our planet back across space and time. And when combined with data from other instruments, such as NASA’s GEDI mission, Landsat data can provide amazing insight into how our world is evolving with us and around us. So let’s take a look into some of the ways Landsat and GEDI data are being harnessed to help us better understand the complex relationship between humanity and nature. Video credit: Chris Burns, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

/// VIDEO SCRIPT ///

We live amongst an intricate tapestry of ecosystems. Dense misty jungles, vast arid deserts, ancient sprawling pine forests. All interconnected, all with a story to tell. Understanding these stories helps us to understand our planet as a whole – how we affect it and how it affects us.

The scientific community has a wide array of methods and instruments to turn to when it comes to gathering data on Earth’s surface, whether from the ground, the water, the air, or… from orbit.

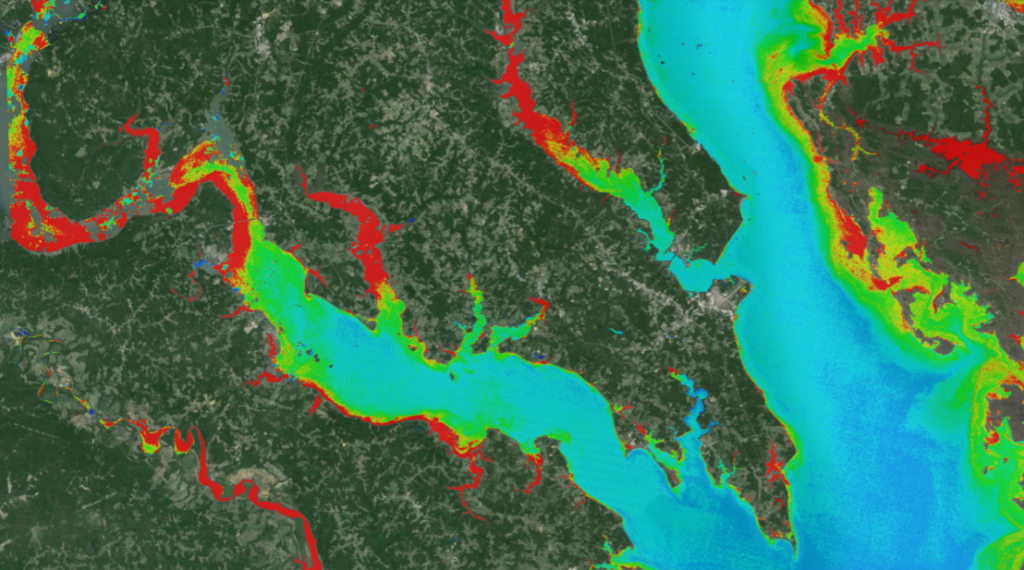

The orbital perspective provided by satellites allows us to see our planet across the spectrum, both visible and non-visible, giving us top-down insight into the health of our forests, temperature fluctuations in our oceans, and the extent of glacial shrinking each year due to melting ice and snow.

Today, Earth’s orbit is bustling with activity, home to thousands of satellites circling the globe each day collecting data. But over five decades ago, let’s just say there was much more room to stretch out.

In 1972, NASA and the USGS partnered to launch Landsat 1, the first civilian satellite designed to image Earth’s land surfaces. Fifty years and eight satellites later, the Landsat program has amassed a vast archive of data on the surface of our Earth, data that’s become the foundation of research into a variety of scientific fields.

From forestry to agriculture, wildlife conservation, and managing natural resources, Landsat’s ability to look back across space and time and provide consistent, freely available data is an invaluable resource for public good.

As useful as Landsat data is on its own, when combined with data from other instruments such as NASA’s GEDI mission, it can be a force to be reckoned with.

NASA’s Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation mission was launched in December 2018 and is the first NASA mission with the primary objective to measure forest vertical structure.

Orbiting over 250 miles above the Earth on the International Space Station, GEDI uses LIDAR technology to record elevation and forest canopy structured data from the planet’s surface.

GEDI emits near infrared laser pulses towards the Earth’s surface and then measures the time it takes for the emitted light to bounce back after reflecting off objects, such as trees, shrubs, and the forest floor. By analyzing the returned laser signals, GEDI provides vertical profiles of forests and topography, a three-dimensional snapshot of not just our forests’ canopies, but also the terrain below, critical information for assessing biodiversity and overall forest health.

And when paired with Landsat’s ability to look back through time and space, GEDI’s 3D vertical perspective can give us an even more detailed picture of our planet’s forests.

Researchers in Italy did just that, combining Landsat and GEDI data to study over 11 million hectares of forest across the Italian Peninsula. Like all ecosystems, forests can be disturbed by a variety of factors, both natural and manmade.

Wildfires, avalanches, disease, and deforestation can all take a toll on a forest ecosystem. The research team combined over four decades of Landsat data with LIDAR data captured by GEDI and aircraft to not only map when forest disturbances across the peninsula occurred, but also what impact these disturbances had on forest biomass.

Their results showed that following a disturbance, it took forests about 15 years to recover, much earlier than the researchers expected. As the climate continues to change, the frequency of these disturbances will be on the rise, which may have an effect on our forest’s capacity to absorb carbon.

Researchers believe that integrating data from different remote sensing sources, such as Landsat and GEDI, could give conservationists a leg up in predicting how our forests bounce back from adversity.

The one constant on our planet’s surface is change. Our ecosystems are perpetually evolving, and for the last five decades, Landsat has been in orbit tracking that evolution.

The Ghanaian forests of Western Africa are considered a biodiversity hotspot – a vast belt of dense forest teeming with an assortment of plants and animals.

The largest intact track of the upper Ghanaian forest can be found in Liberia, where it plays a critical role in the country’s economy. Liberia’s forests are major sources of important commodities, such as cocoa, rubber, and palm oil – commodities that have, unfortunately, been a major driver in increased land cover change.

Researchers wanted to know how much Liberia’s forests had changed over a 19-year period, and also what effect these changes had on the forest ecosystem. So, naturally, they turned to Landsat and GEDI.

They analyzed Landsat imagery collected between 2000 and 2018 as well as GEDI tree height data to map the extent of land cover change over this period. The results showed a significant increase in forest fragmentation over the past two decades.

Over 14% of dense forest areas, which are essential for biodiversity and carbon storage, were degraded and GEDI-based measurements from 2018 showed a substantial reduction in forced height and canopy closure when forests transition to more open classes.

Researchers believe their method of fusing Landsat and GEDI data can not only provide the government of Liberia a roadmap to measuring broad changes in their ecosystems over time, but also help to better inform decisions on managing their natural resources going forward.

Wildfires are often a natural occurrence in forests worldwide, part of the forest’s lifecycle, helping to clear out old growth

to make room for new growth. But increased drought and deforestation has in turn led to an increase in not only the frequency of wildfires, but also the severity.

There is, however, an area on Earth where wildfires can take on an even more dangerous quality – Chernobyl, site of the worst nuclear disaster in the history of the world.

Following the disaster in 1986, the Soviet government established the Chernobyl exclusion zone or CEZ, a thousand-square-mile area surrounding Chernobyl deemed too radioactivefor human habitation.

Almost 40 years later, the CEZ is still largely uninhabited, home to dense forest that has surprisingly become a haven for wildlife. Like other forests, Chernobyl’s forests too are prone to wildfires, wildfires that can potentially release hazardous radiation into the atmosphere.

Simulating wildfire behavior is a necessary tool for examining the efficiency of fuel treatments, such as controlled burns, but it requires up-to-date maps of both fuel types and canopy metrics, data not readily available for many areas in Ukraine, including Chernobyl.

To make up for this dearth of information, Ukrainian researchers developed an approach for updating fuel maps using freely available Landsat and GEDI data. They fed Landsat data collected over a 12-year period along with GEDI data through a machine learning algorithm to produce an accurate map of fuel types and canopy metrics across the Chernobyl exclusion zone.

The researchers believe that the union of remote sensing data from the likes of Landsat and GEDI could provide an effective method for updating fuel maps, particularly in radioactive areas like Chernobyl, where collecting fuel data can be both impractical and downright dangerous.

These three case studies make it abundantly clear that Landsat and GEDI make quite the dynamic duo.

Following four years of service aboard the International Space Station, NASA announced a pause in GEDI’s mission earlier this year. But GEDI’s tour of duty isn’t quite up just yet. NASA plans to resume operations sometime in 2024 with potential plans to continue collecting data until 2030. And when GEDI is back online, Landsat will be there to once again join forces.

The partnership between Landsat and GEDI isn’t just about data – it’s about our planet’s future. From the dense jungles of West Africa to the gentle forested hills of Tuscany, Landsat and GEDI are helping us understand the complex relationship between humanity and nature, giving us a clearer picture of our planet’s health and how we can better protect it, allowing us to see the forest for the trees.